JULIUS HIRSCH: Died not wanting to believe

“How could you forget? After all, it was only fifteen years ago that we were fighting for what we believed was our nation, dying in the trenches to try to win a war that none of us wanted but which we went to fight anyway. How could you accept this nonsense? I can no longer even continue to work in football for the team that I have served faithfully for all these years. I want to be as clear as possible: you are all doing irreparable damage to this country and to those who have served it and loved it.

It is 1933 and all German teams have been ordered to expel Jewish footballers, coaches and collaborators from their ranks.

Julius Hirsch is one of them.

The above are some of the sentences he wrote to the Karlsruher management at the time of his forced farewell.

He is now a coach in the youth sector but cannot accept such a thing happening in ‘his’ Germany.

The worst is yet to come, however.

With the promulgation of the racial laws in 1935, the Nazis make their intentions crystal clear: there is no longer any place for Jews in the life of the country.

His friend and teammate Gottfried Fuchs, who won the 1910 German championship with him in Karlsruher, suggested that he flee to Canada with him.

‘There is no place for us here any more, things can only get worse,’ his friend tells him.

Julius Hirsch does not believe this, he just does not want to accept that his people could have forgotten everything so quickly. He had fought for Germany in the First World War, even earning the Iron Cross for his courage.

He, who had lost a brother in that war.

And then the matches, triumphs and goals with Karlsruher, SpVgg Fürth and even the German national team where he made his debut at the age of eighteen.

He even married a German woman and was convinced that all this madness had its days numbered.

In 1938 his two children, Esther and Heinold, are expelled from school.

He decides to move to Paris with his wife Ella Karolina Hauser and their children.

“Waiting for everything to return to normal”.

Normality will never return.

What convinces Hirsch to return to his homeland a few months later is frankly impossible to know.

Germany is at war and within a few years what seemed like an easy victory turns into a nightmare for the German people.

In 1939, in a last desperate attempt to save his family, Julius Hirsch decides to divorce his beloved Ella.

‘Maybe at least they will be left in peace’ is what Julius thinks in those dramatic days.

Instead, the situation precipitates.

Julius no longer has a job.

In 1943, a letter arrives from the Gestapo inviting him to report to their headquarters in Karlsruhe for an unspecified ‘professional assignment’.

For him there will only be a train to Baden first and then to Auschwitz, the infamous concentration camp.

It is the first of March 1943.

Two days later he manages to write a letter to his children.

It is postmarked 3 March.

“My dears. I have arrived at my destination. Everything is going well. I am in Upper Silesia. Take care.”

Of Julius ‘Juller’ Hirsch, one of the most talented and gifted number ’11’ in the entire history of German football, there would be no further news.

Only in 1950, exactly one lustre after the end of the war, would a date of death be declared for Julius Hirsch: 8 May 1945, several months after the evacuation and liberation of the Auschwitz concentration camp by the Red Army.

His name does not appear in the Auschwitz records and many believe that Julius Hirsch’s life actually ended in a gas chamber a few days after his arrival at the concentration camp.

He had believed that it would not have been possible to go this far, that the collective madness that the Austrian ex-painter and ex-soldier had skilfully constructed would end up falling like a house of cards.

He was wrong.

And he paid for his error of judgement with his life.

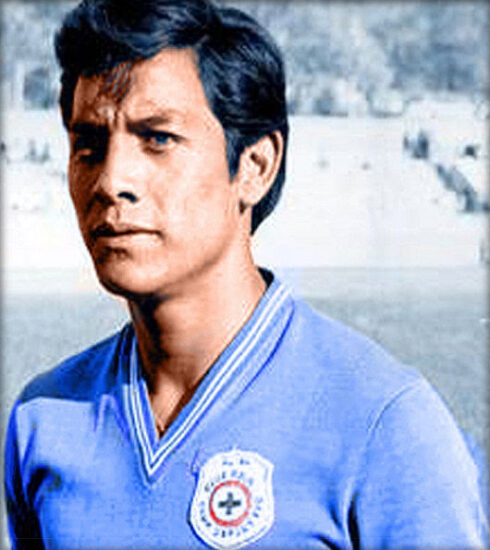

Julius Hirsch was born in Achern in 1892 and has played for Karlsruher FV since he was ten years old. He is really good at playing football. So good, in fact, that at the age of just seventeen he became an indispensable member of the first team of the South German Rossoneri.

At that time, Karlsruher FV is a real team.

He won three South German regional championships (the Südkreis-Liga) between 1910 and 1912 and in 1910 even won the national title, the first and only one in the club’s history.

Hirsch was part of a trio of outstanding strikers.

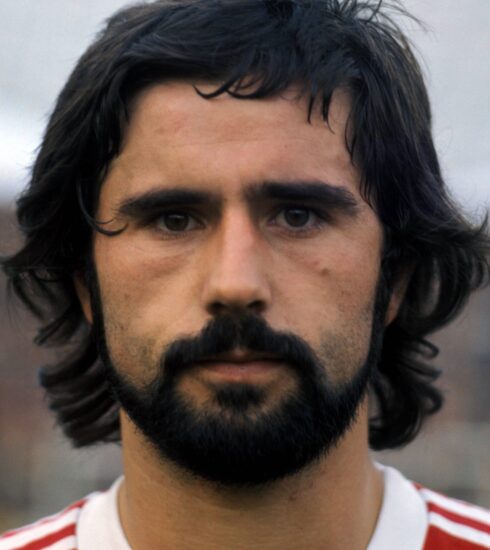

Together with Fritz Förderer and Gottfried Fuchs, he became one of the protagonists of German football at the time. Julius, who everyone called ‘Juller’, was a left winger with great technical skills and a precise and very powerful shot.

In 1911 he received a call from the German national team.

He will be the first Jewish footballer to wear the white Teutonic jersey with which he will participate in the 1912 Olympic Games in Sweden, although the experience will certainly not be unforgettable: a five-to-one defeat against his Austrian ‘cousins’.

That same year, however, he performed a remarkable feat: he scored four goals in a match against Holland with his national team and his name became popular throughout the country.

In 1913 he left his Karlsruher team to move to SpVgg Fürth and the following year he won his second German championship title with them … shortly before ending up in the trenches for four long years at the outbreak of the First World War.

On his return he would play another season at SpVgg Fürth before returning, in 1919, to Karlsruher where he would stay until the end of his career in 1925 when he was thirty-three years old.

He would then remain at the club as youth coach until that day in 1933 recounted at the beginning.

ANECDOTES AND CURIOSITIES

Julius Hirsch’s two children, Heinold and Esther, were also imprisoned in the first weeks of 1945 in the Theresienstadt ghetto, but fortunately they were luckier than their father as they were freed by the Soviets in May 1945.

Gottfried Fuchs, a great friend of Hirsch, tried hard to convince him to follow him to Canada. He too, like Hirsch, had made his debut in the German national team at a very young age and the chemistry on the pitch between the two was consecrated. Fuchs held an enviable record for almost ninety years: that of the player with the most goals scored for his national team. During an Olympic qualifying match in Stockholm, Germany defeated Russia 12 goals to nil with Fuchs scoring ten of the goals.

This record stood until 2001 when Australia’s Archie Thompson scored thirteen in the same match … won by his national team 31 goals to nil against American Samoa.

Some sources say that during the journey to Auschwitz one of the train drivers, a football fan, recognises Julius Hirsch. He tells him where he is being taken and offers him the chance to escape. This time Hirsch does not accept. His faith in the Germany he had fought for was unshakeable.

It was his last chance.

Since 2005, the German Football Association has awarded a prize in Hirsch’s name, which is given to those who set examples of tolerance and integration in German football.

The first of these was awarded to Bayern Munich for organising a match between their Under-17 team and a youth selection consisting of Israeli-Palestinian players.

In Karlsruhe, for some years now, there has been a street named after Julius Hirsch in the vicinity of where the old football pitch that saw him in action used to be.

A fitting reminder of a man who trusted his compatriots …