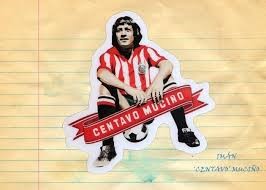

OCTAVIO ‘EL CENTAVO’ MUCINO The tragic death of a great goalscorer

Taken from http://www.urbone.eu/obchod/storie-maledette

I was right.

They were wrong about me and I couldn’t be happier!

At Cruz Azul, the team where I have been playing for the last four seasons, they thought my recent knee problems were unfixable and that I had already given my best.

And to think that I have just turned 24!

And to think that we have won three championships in the last four years!

But no one forced me to leave.

It’s just that if I don’t feel complete trust in me, I prefer to go elsewhere.

We strikers are like that.

Trust is everything … we need it.

So I came up here to Guadalajara.

To Chivas.

A glorious team with a fantastic crowd.

They come from difficult years.

A couple of seasons ago they even risked relegation.

Unthinkable for a club of this calibre.

Even this year, in my first championship with the ‘Rebano Sagrado’ (the sacred herd), we didn’t make waves.

Personally, however, I am really happy.

They welcomed me with incredible warmth right from the start.

And right from the start I felt at home.

Of course that goal against America!

A diving header.

A ‘palomita’ as they call it around here.

I scored 14 more, but none as important as that one.

The winning goal in the Mexican ‘Clasico’ is priceless!

Even in the national team they continued to believe in me.

Unfortunately things didn’t go well there.

In a fortnight the World Cup will start in Germany, but Mexico will not be there.

Haiti arrived ahead of us in the qualifying round.

A catastrophe for a people like ours where football is much more than a game.

All this only four years after we hosted the World Cup.

But we must look ahead.

To next season with Chivas for a start.

The glorious ‘Rebano Sagrado’ MUST return to the top of football in the country.

The fans demand it, the president and directors demand it, we players demand it … the history of this great club demands it.

And I, with my goals, will do everything I can to make this happen.

It’s a warm late spring evening.

And it’s Saturday night.

We are in Guadalajara.

Octavio “El Centavo” Mucino is having dinner at “Carlos O’Willys”, one of the hottest restaurants in town.

With him are three friends with their wives and girlfriends.

He is one of the idols of ‘Chivas’, the city’s main team.

He arrived the year before, from Cruz Azul, where he contributed with his goals decisively to winning the last two championships.

He is 24 years old.

He is an excellent centre forward and a lot of hopes are pinned on him by the fans of the ‘Rebano Sagrado’, the very popular Mexican club.

The season ended two weeks early.

It was not exciting, but those are difficult years for Chivas.

And thank goodness for ‘El Centavo’, the little guy, so called since childhood not so much because of his short height (he is 172 centimetres tall) but because given his precocious talent as a child he was always played with boys of a higher category and he was regularly the smallest one on the field.

At the table next to him were some young boys, smartly dressed in their fashionable Italian suits and with their customary Rolexes on their wrists.

Sons of the local upper middle class.

No doubt about that.

They are just a little exuberant at first.

They recognise Octavio.

They are fans of Atlas, the other team from Guadalajara.

A few teenage shenanigans, some teasing and a bit over the top.

The alcohol, however, increases the intensity of the shouting, laughing and bragging.

Soon the jeers turn to insults.

The owner of the club intervenes, inviting the boys to calm down and restrain themselves a little.

He is a small, mild and peaceful little man.

His far from slender physique and a neatly trimmed moustache make him look a lot like Chico, Zagor’s fellow adventurer, a very popular comic strip at the time.

His intervention, however, only adds to the boys’ arrogance.

Now they are really getting heavy.

There’s one of them in particular, Jaime Muldoon Barreto, who rises up a bit as top dog and by dint of insults ends up making Octavio and his friends lose their patience.

It is Octavio himself who gets up from the table at the umpteenth provocation.

The two quickly move from words to deeds.

Octavio, who boxed when he was very young, dodges Barreto’s first clumsy attacks without any problem.

Then he takes the boy by the lapel, lifts him up and, speaking to him a few centimetres from his face, says, ‘Chiquito, don’t confuse me with someone else … you are a kid, so go and get into trouble with other kids … not with me and not in here’.

Jaime Muldoon Barreto, his pride evidently hurt, reacts.

He launches a punch, clumsily, which barely reaches the target.

Then he starts with a series of kicks, but again with little result.

Octavio then blocks him for the second time, takes him by the lapel again but this time accompanies this gesture with a slap.

Not a punch, as between men.

With a slap, as one does with children who are too capricious and impertinent.

At that point, Octavio’s friends intervene, as do Barreto’s, who, having come to their senses, help to restore calm.

Everyone sits down at their own table.

Everyone finishes their dinner

Everyone resumes the classic chatter of an evening in a restaurant.

All is well.

All returned.

It is now closing time.

The last to leave the restaurant are “El Centavo” and his group.

Outside the club, however, there is still Barreto, with his friends, leaning against a red Galaxy.

Octavio sees them, approaches the guys.

He extends his hand towards Barreto.

“What was was boy … no hard feelings.”

Only there is still resentment … and lots of it.

Jaime Muldoon Barreto pulls out a gun and fires three shots towards Octavio Mucino.

The first hits him in the chest, the second in the shoulder, but the third hits him in the head, on the temple.

It takes everyone a few seconds to realise.

To realise that something serious, something irreparable, has just happened.

Jaime Muldoon Barreto gets into his car and with other friends sets off at full speed.

One of Octavio’s group tries to grab onto the car door, but after a few metres he has to let go.

A vigilante on guard duty at the restaurant pulls out his gun and tries to shoot at the car of the Guadalajara ‘coolies’, but without success.

Octavio ‘El Centavo’ Mucino died two days later, never having regained consciousness.

The murderer, the young Jaime Muldoon Barreto, son of one of the richest industrialists in Guadalajara, will first be helped to flee abroad and when he returns to Mexico two years later, he will be declared ‘No era responsable de su actos’ (our ‘incapable of understanding and wanting’) at the time of the murder because the drugs prescribed to the young man to cure his epilepsy, taken with large quantities of alcohol, rendered him incapable of answering for his acts.

Once again, money shifts the balance of the law and a murderer goes unpunished.

It will be the whole of Mexico that will mourn the loss of one of its best footballers.

It will be his national teammates, those of Chivas and his old teammates of Cruz Azul.

All of them deeply attached to this striker with the face of an Indian, always smiling, joyful and with a ready wit.

Who, in the cancha, knew how to get out of the way with incredible intelligence, could always be found in the right place in the penalty area and who, with his explosiveness, would take off and score wonderful headers, despite his 172 centimetres.

He leaves behind his wife and little Octavio Junior, just 1 year and 3 months old.

Octavio ‘El Centavo’ Mucino, killed by a stupid daddy’s boy so stupid that he refused a gesture of peace.

Convinced that his own pride was worth more than a man’s life.