PAUL LAKE: What am I doing here?

«I feel like an outsider.

I’m here for the classic team photo on the first day of pre-season.

I’m here … but I’m not really here.

This comedy has been going on for years now.

And every year I feel more and more useless, out of place.

I almost feel ashamed.

I haven’t really done anything wrong… on the contrary.

I really have tried them all since that bloody late summer day at Villa Park in Birmingham.

It was 5 September 1990.

I was 21 years old.

Howard Kendall had handed me the Manchester City captain’s armband.

The only team I had ever played for.

The only one I cared to play for.

A few months earlier was the World Cup.

It was really close that I wasn’t in the 22 who got on the plane to Italy.

Only in the last game with the National B team before the call-up, that old sclerotic who was our selector decided to play me on the left wing against Ireland.

I left wing!

I have played and can play anywhere … except left wing and centre forward.

That’s how I gambled my chances.

But I got over it quickly!

At 21, there’s plenty of time.

Instead my time started to run out on 5 September 1990, on the pitch at Aston Villa.

A clean, perfectly-timed strike on Tony Cascarino.

Only the studs plant themselves in the ground … while the rest of the leg pushes forward.

In the contrast of forces I feel a pain in my knee.

Excruciating, terrible.

I stay on the ground.

“It’s a fucking ligament sprain,” I think.

Something similar had happened to me two years ago against Bradford.

Although the pain wasn’t even comparable.

The amazing (!) Manchester City medical staff decide to have me x-rayed.

“Nothing broken, Paul ! In less than two months you’ll be on the pitch”

Only, as soon as I try to run again, the pain returns stronger than before.

They decide to give me an arthroscopy.

The anterior cruciate ligament is ‘gone’.

The first attempt at reconstruction fails miserably.

As soon as I return to training, the ACL goes again.

18 operations. You read that right. Eighteen.

Almost as many attempts to return.

Less and less convinced, more and more forced.

I don’t believe it any more … how can I believe it?

And again this pathetic pantomime!

The group photo with all my teammates, some of whom don’t even know who I am and have never even seen me play.

What am I still doing here?»

Paul Lake since that cursed September 1990 has really tried everything to get back into football.

This is the story of a boy who loved City, who even as a child would go to the stands at Maine Road to cheer on the Blues.

Manchester City, which except for a few brief periods in its history has always been in the shadow of the more followed, loved and successful Manchester United.

But which has a loyal, passionate audience like few in England, which has always packed the stands at Maine Road despite the fact that for so many years its supporters have always felt like a rollercoaster.

One moment there at the top almost touching the stars alongside England’s greats and the next having to sweat their way back into the First Division at Barnsley, Hull or Bournemouth.

It was during one of those periods that this little story was born.

That of a player as precocious as he is crystalline, with unlimited possibilities who, little more than a teenager, had already put the captain’s armband on his arm in the team he loved, the only one he was interested in playing for.

Liverpool, Arsenal, Glasgow Rangers … even Manchester United had tried to take him away from Maine Road.

No dice.

“And at Manchester City I want to play. Possibly forever.”

Howard Kendall, at the start of the 1990-91 season doesn’t think twice.

A five-year contract and captain’s armband … to Paul, who was 21 years old and when in the team there were players like Peter Reid or Colin Hendry, who had played dozens and dozens of games with the respective national teams of England and Scotland … and were at least 10 years older than him!

But on that cursed evening in September 1990, luck turned its back on him completely.

It seems a very normal, almost banal operation.

Instead, his knee shattered into a thousand pieces.

The cruciate ruptured and with it Paul’s career.

It would be five interminable years where he would go from captain and undisputed idol of the Manchester City fans to feeling a burden on the club.

A club that will not do much in those years to earn Paul’s esteem.

A club that, when it finally lost faith in his complete recovery, made him go through humiliating experiences such as when, after the umpteenth operation on his battered knee (it was his teammates who, through a collection, paid for the plane ticket for Paul’s girlfriend to accompany him), the club made him return to Economy Class, on crutches and in a seat too narrow for his 185 centimetres and his knee in plaster … with the club doctor comfortably seated in Business Class …

Added to all this will be the shame of landing in Manchester and also having to look for a rented wheelchair with which to get to a taxi …

As said, there will be many attempts.

This writer had the chance to see one of the first ones live, the one where hope was still alive.

It was on the first ‘Monday night’ of English football.

It is August 1992 and it is the first of the championship.

It is played at Maine Road and the match is Manchester City vs QPR.

Paul is on the pitch, wearing his beloved number 8.

He has done all the preparation, through ups and downs, but finally looks good.

Peter Reid, City’s manager, will call him ‘the most important purchase of the summer’ so great is the satisfaction at having Paul back.

Paul plays great for an hour.

He even plays in attack this time.

Alongside Niall Quinn and moving as a second striker, acting as a reference for the midfielders and moving all over the attacking front.

After an hour of the game, however, Paul holds his knee … he calls for a change.

He comes out on his feet, albeit with a slight limp.

The Maine Road holds its breath.

After the match Paul will say that his knee isn’t right, it has swelled up a bit and he doesn’t feel too confident.

Three days later Manchester City travel to Middlesbrough.

Paul is nevertheless sent out from the start.

His game lasts a good three minutes … before his cruciate ligament ruptures for the third time.

One more attempt playing with the reserves in 1994 and then all possible and imaginable more or less desperate appeals such as acupuncture and various witch doctors with their miraculous waters and prayers.

Paul falls into a terrible depression.

Every single day he has to take painkillers to manage to have any semblance of a normal life.

He is taken off football, too soon to think about what else to do with his life.

In 1995 he gets married, has a son but his marriage falls apart after a few months.

Manchester City, however, finally remembers him and offers him a job at the club.

He does a course as a physiotherapist and starts working on the Manchester City medical staff.

This is exactly what Paul needs.

Fortunately, his ghosts slowly leave him.

A new love story arrives.

He marries Joanne and two children arrive.

Life begins to smile on him again.

Now Paul, after acting as an ‘ambassador’ for Manchester City in the community occupies the same role this time for the Premier League, going around the UK and the world to promote what for many is now the most beautiful league in the world.

There are very few who remember him as a player but there are many, far more knowledgeable than myself, who describe him as potentially the most complete player to emerge from English football in the last 30 years.

The irony with which Paul looks back on that period is beautiful

“Every so often I’m asked what I would save from those bloody 90s … actually two things are there.

The birth of my eldest son Zac and my first Oasis concert … “

ANECDOTES AND TRIVIA

With the premature end of his career, a dramatic period begins for Paul.

He falls into depression and there are really difficult times for Paul.

One evening, his trail is lost. The police find him stranded on a motorway bridge.

“I had no intention of jumping off,” Paul later recounts, “but it is also true that I really didn’t know where to go or what to do with myself.

On one occasion he turns up at a monastery.

He goes to seek comfort and help.

But he is so ashamed and afraid of being recognised by anyone.

That is why he carries a blank cheque in his pocket so that if they recognised him he could say he was only there to make an offering …

His favourite refuge during the difficult years when he was desperately trying to come back after his terrible injury was the cinema. “With my Coke and popcorn I could stand there alone for hours without being recognised by anyone and without having to speak to a soul.

Even attending ‘his’ Manchester City matches after a while became a problem.

“There was always some idiot telling me how lucky I was to be paid not to do shit,” Paul recalls not without rancour. “At that point I would make up an excuse and leave for the toilet to try and calm down to resist the temptation to punch someone.”

Telling of his return from surgery in the United States in ‘Economy’ class having to keep one operated knee bent for several hours to such an extent that on arrival at Manchester airport Paul could not even stretch his leg, another humiliation came shortly afterwards, at the time of his divorce: without the match premiums it had become impossible to pay the rent of the house where he lived with his wife so Paul, at 25, had to move back in with his parents.

Of course, there are not only the negative memories. In the few years that Lake played there are several occasions when the memory is sweet and positive.

Perhaps no memory is as sweet as the fantastic 5-1 derby victory against bitter rivals Manchester United on 23 September 1989.

“It was the best day of my career. We played the perfect game. Us, a team of kids against Ferguson’s Manchester United who had players in their ranks worth Paul Ince, Viv Anderson, Gary Pallister, Mark Hughes and Brian McClair. I remember that day when I was driving to the stadium I had to stop at a traffic light. A dad was walking alongside with a boy aged 7-8 at the most, both wearing City shirts and scarves.

The father recognised me and pointed me out to his son.

The only thing they did was join hands as if in prayer, saying only ‘please … please … please’.

That match has a special place in Paul’s memories and those of all the Manchester City people, who in those years were far from the standards of United’s city rivals.

“Before we took the pitch we were all nervous and worried. We would all have signed for a draw. The start was very difficult. In the first quarter of an hour they crushed us. Their goal seemed only a matter of time. Then it happened that some of their fans entered the pitch and the game was suspended for a few seconds. Our coach Mel Mechin and coach Tony Book brought us together, gave us some pointers and heartened us. When the game resumed we were simply 11 different players. We did not lose a single tackle or aerial duel for the rest of the match.

On our fifth goal there wasn’t a single United fan left inside the stadium.”

From that historic day remains the end-of-match interview for the local radio station.

When asked what the secret of Paul’s victory and fantastic personal performance was, Lake’s answer was “I ate raw meat for breakfast!”

One of Paul’s greatest admirers was Howard Kendall, the great English coach who led Everton to the title and Cup Winners’ Cup in the mid-1980s and who was coaching City at the time of Lake’s injury against Aston Villa.

“In the summer of 1990 there were several big teams who asked me for Paul Lake. To all of them I replied that the figure for his signing fee was £10 million.”

“But how?” my interlocutors replied astonished. “Nobody has ever bought a defender for more than £2.5 million! How can you ask for that kind of money ?”

“Simple. Because I don’t want to sell Paul Lake,” was always my answer.

Paul Lake is, as they say in Britain, a ‘cult hero’ or one of those players who were so loved that they became legends, regardless of the seasons they played for the club, their trophies or their exposure in the media.

Paul Lake was a great player, with immense potential who was robbed by misfortune of his chance to become the flag-bearer of his beloved Manchester City and, without a shadow of a doubt, of the English national team.

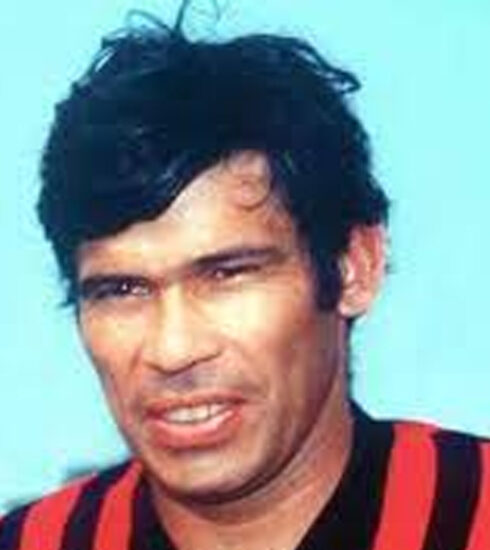

Below are pictures of the injury that ended up costing this talented youngster his career.