NICOLAE DOBRIN: The forgotten genius of the ‘Wizard of the Ball’

Romania qualified for the 1970 World Cup in Mexico.

This is a historic achievement.

Not since 1938 has this country’s national team played in a World Cup final. To do so, it got the better of Greece, Switzerland and, above all, Portugal of Eusebio, Torres and Hilario, the big favourites in the group.

It was precisely the match against Portugal, played in Bucharest on 12 October 1969, that the Romanians regarded as decisive, even though Greece was proving to be a tougher bone than expected.

The first leg in Portugal a year earlier was a rout.

A zero-three that severely questioned Romania’s chances and especially the already low self-esteem resulting from years of ‘lean cows’ at international level.

Subsequent victories against Switzerland (both first and return) and the painful draw in Greece, however, put the Romanians back on track and they now have their destiny in their hands in the last two home matches, the first against Portugal and the next against the surprising Greeks of Dimitrios Papaioannou and Giorgos Koudas.

Portugal is beaten by one goal to nil. The decisive goal was scored by number 8 Nicolae Dobrin. His diagonal right-footer was only touched by Vitor Damas, the Lusitanian goalkeeper, but ended up in the back of the net.

It was to be the winning goal, the one that allowed Romania to face Greece in the last qualifying match with two useful results at their disposal.

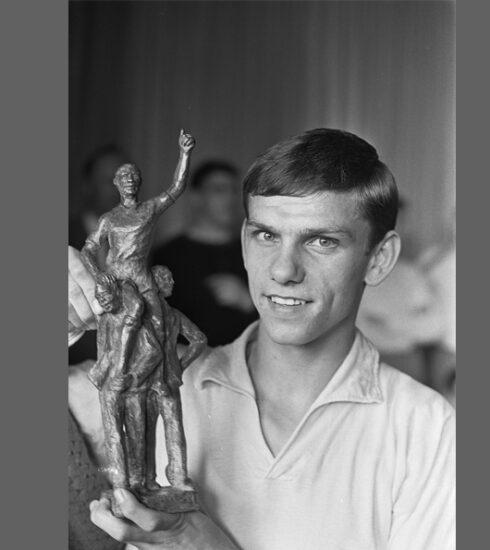

The absolute protagonist of that match is him, the Arges Pitesti schemer Nicolae Dobrin.

He will be the inspiration for all Romanian manoeuvres. He is what one calls a complete midfielder. He has an extremely refined technique, kicks with both feet, goes past players with extreme ease and does not disdain covering and recovering the ball at all.

He has already been voted the best Romanian footballer two years in a row (1966 and 1967) despite not playing for any of the capital’s great teams (Steaua or Dinamo) and he is the man in the national team responsible for triggering the two strikers Florea Dumitrache and Mircea Lucescu.

With Greece came just enough of a draw to guarantee qualification. Emeric Dembrovschi’s goal was only answered by Dimitris Domazos.

Romania returned to a World Cup final.

An entire country celebrates this great and unexpected result.

The team is solid, organised and Nicolae Dobrin is the thinking brain.

“We are not going to Mexico to be tourists!” Angelo Niculescu, the coach of Romania, said bluntly and unequivocally … although fate would certainly not lend the Romanians a helping hand, putting them in the same group as the two big favourites of the event, Brazil and England.

Nicolae Dobrin is not exactly ‘a saint’. He loves playing football but in his own way. Tactics, physical preparation, pre-match retreats and discipline are not exactly in his wheelhouse. And while in little Arges Pitesti, the team where he has always played, he has complete freedom of expression and even a certain tolerance for his off-field activities, things are quite different in the national team.

His relationship with Niculescu can hardly be described as idyllic.

So far, the two have managed to tolerate each other.

There was a common goal to be achieved.

But the ‘truce’ lasted very little.

The Romanian national team is on the plane that is taking them to Mexico for the final phase of that longed-for World Cup.

Nicolae Dobrin decides to take advantage of the plane’s bar service.

For the entire journey.

The warnings and disapproval of Niculescu and the other Romanian directors are to no avail.

When the delegation arrives in Mexico Nicolae Dobrin is so drunk that he cannot stand up.

Niculescu is on a rampage.

Discipline, the concept of ‘group’ and respect for rules are fundamental to him.

Nicolae Dobrin, the strongest Romanian footballer at the time at the 1970 World Cup in Mexico, will not play a single minute at that event.

Romania will play an excellent World Cup, losing narrowly to both England (0:1) and Brazil (2:3) while playing an excellent game against the Brazilians. In the other match of the group they got the better of Czechoslovakia by two goals to one.

On their return, the Romanians were welcomed with full honours for their brilliant performance.

But there are many observers and fans who will ask “but with Dobrin on the pitch, how would it have turned out?” …

Nicolae Dobrin was born in Pitesti on 26 August 1947.

At the age of eleven, he entered the club’s youth sector.

There is no one in the city who has a single doubt: such a good boy with the ball between his feet in those parts has never been seen before.

For him, the debut in the first team comes at an age when his peers are still in compulsory school and are growing up in the junior team of a club.

Nicolae played his first official match when he was 14 years and 10 months old.

It is the first of July 1962 and the club is still called ‘Dinamo Pitesti’ and will only take the definitive name of ‘Arges’ from 1967.

Dobrin has everything it takes to play football. His technique is top-notch and he has dribbling as his defining characteristic. He moves with great elegance and always plays with his head held high, like all great ‘directors’ in the history of football. Supporting these talents is also a respectable physique: Dobrin is six feet tall and not at all afraid of tough opposition.

His debut in the national team came when Dobrin was not yet nineteen years old.

He would play 47 times for the Romanian national team, scoring six goals but never having the chance to show off in a top international tournament … which is why his name would never be known at world level despite being considered one of the strongest footballers ever in his country.

He would play his entire career for Arges Pitesti, which, thanks to him, would win the only two titles in the club’s history.

The first title would come at the end of the 1971-1972 season. For the town that is home to the car manufacturer ‘Dacia’, this is a historic achievement. Nicolae Dobrin is to everyone ‘vrăjitorul balonului’ or ‘the wizard of the ball’.

He practically has the keys to the city … and it is the bars of Pitesti in particular that will welcome him warmly and with special attention.

The title won gives the ‘white-violet eagles’ the chance to play in the Champions Cup the following season.

In the first round, Dobrin and his team-mates ‘drew’ Bonnevoie, a small team from Luxembourg, who were buried by goals (six to zero the total of the two matches).

In the next round, the Romanians fell to the mighty Real Madrid of Pirri, Amancio and Santillana.

In the first leg in Romania, a miracle happens. Little Arges wins by two goals to one. Dobrin scored the first goal on a penalty kick, and after Anzarda’s temporary equaliser, it was midfielder Prepurgel who gave his team an unexpected victory.

However, no one had too many illusions. On the return trip to Spain, Real Madrid will have an easy time against the Romanians.

That will not be the case at all. Santillana’s initial goal was answered by Radu at the end of the first half. At the start of the second half, it was Grande who put his team back in the lead. The result would remain at two to one throughout the second half and only a Santillana goal three minutes from the end allowed the ‘Merengues’ to avoid extra time.

However, at the end of that very tight match, something happened.

Real Madrid’s wealthy and powerful president Santiago Bernabeu was fascinated by Dobrin’s talents. He wants him at all costs at his Real.

A long and exhausting negotiation with the Romanian authorities begins.

Apparently, Bernabeu talks directly with Nicolae Ceausescu, the President of the Socialist Republic of Romania, going so far as to offer him two million dollars to have Nicolae Dobrin in Madrid.

Ceausescu is adamant. The rules for Romanian footballers are clear: it is impossible to transfer abroad until the age of 30.

Nicolae Dobrin is only 25.

Santiago Bernabeu is used to getting what he wants.

The best footballers have to play for his Real.

Another opportunity presents itself.

On 15 December of that same 1972, the farewell to football of Paco Gento, the brilliant right winger of the ‘great Real’ who had dominated international football in the first part of the previous decade, is celebrated. Invitations flooded in for the greatest champions of Eastern Europe, all top quality footballers and all in Bernabeu’s good graces.

Besides Eusebio, who arrived from neighbouring Portugal, there are Yugoslavian left-winger Dragan Dzajic, Hungarian striker Ferenc Bene and, of course, Nicolae Dobrin.

Dobrin stayed in Madrid for about ten days (the championship in Romania is at a standstill for the winter break) and Bernabeu tried in every way to convince the midfielder to stay in Madrid, promising to personally solve all the bureaucratic troubles that would result.

Nothing comes of it.

After the game, Dobrin would return to his Pitesti club to stay there until 1981 and, after a small, one-off spell with FCM Targoviste, return in 1982 to end his career with the club he loves the following year.

When his career as a footballer was over, Nicolae Dobrin undertook his career as a coach and here too it was his Arges team on whose bench he would sit for most of his career.

Nicolae Dobrin died in October 2007, aged just 60.

A lung tumour took him away.

At his funeral in Pitesti there will be more than five thousand people to bid farewell to their leader for more than twenty years.

The ‘Prince of Trivale’ (named after the neighbourhood where he grew up) is for many of those who saw him in action considered the best Romanian footballer of all time.

«Hagi was a phenomenon. But he only had one foot. Dobrin was a ‘magician’ with both».

ANECDOTES AND CURIOSITIES

One of Dobrin’s best friends at Arges was Viorel Kraus, who played with Dobrin between 1967 and 1969. Kraus recounts that even then, when Dobrin was in his early twenties, it was very difficult to keep him at bay. More than once the young midfielder made his tracks disappear and his teammates often went to pick him up in clubs late at night or had to go to his house on match day to get him back on his feet. “Dobrin was every time deeply sorry for his behaviour and begged the managers and coach to forgive him and put him on the pitch anyway!” recalls Kraus.

Who then adds “the point was that with him on the pitch we were a completely different team!”

And every time, Dobrin would repeat the same phrase just before taking the field, ‘To make it up to me today, I have to play a great game …’ and most of the time, that is exactly what happened!

In the year of the first title for Arges, the decisive match turned out to be the penultimate one, away against Crisul Oradea, a team that had already been relegated. Dobrin was simply irrepressible that day. He scores the first two goals himself and provides the assists for the other two in the four-goal to one victory that will deliver the first title in its history to the little club from Pitesti.

Much more dramatic and sensational was Arges Pitesti’s second (and, at the time, last) title win at the end of the season in the 1978-1979 season, after a long ‘war’ against the capital’s two big boys Steaua and Dinamo.

It was against Dinamo Bucharest that Arges sealed its triumph.

It was 24 June 1979 and in the stadium packed with more than 20,000 spectators at Dinamo Bucharest, the hosts and Arges Pitesti would give life to a match considered by many in Romania to be the most exciting in the entire history of football in that country.

Dragnea’s opening goal for Dinamo was answered by Radu II (with a brace) and Joita, putting Arges ahead by three goals to one with twenty minutes to go. Dinamo did not stand up to it and with Dudu Georgescu first shortened the distance in the 76th minute on a penalty kick and then one minute from the end brought Dinamo’s ‘red dogs’ back to parity. At this point, however, Dobrin, not satisfied with having inspired all his team’s manoeuvres and having provided the assists for two of the three goals scored by his team, decided to put the classic ‘icing on the cake’ to an already memorable match.

We are already in the second half when Dobrin, on a support from the wing, placed on the edge of the opponent’s area, lets off a right outside shot, whose trajectory goes off into the back of the Dinamo net, sealing the title for Arges Pitesti.

On what happened regarding the failed transfer to Real Madrid, it was Dobrin himself who explained things very clearly a few years later.

“The responsibility for that non-transfer can be divided in half between Ceausescu and … myself! Ceausescu considered me a symbol of our country and could certainly not allow my transfer to a country with a fascist dictatorship in power. I then loved my city and with a wife and a small child, it didn’t seem right for me to face such a major change” recalls Dobrin, who then adds.

“In Pitesti, I could live the life I wanted … and I also had my wine and my ‘sarmale’ (a traditional Romanian dish) … no, I was too well off in Romania!” is what Dobrin has always said.

There is, however, another reason, which emerged later in the years. During his stay at Real Madrid with whom he trained for about ten days ahead of the match in honour of Gento, Dobrin was not particularly impressed by the training system then in vogue at Real Madrid.

Dobrin himself recounts.

“Miguel Muñoz used to work a lot without the ball. Running, running and more running. Lots of tactics and also three-touch matches were played and dribbling was forbidden except in the last 25 metres. I felt like a robot. No, that football wasn’t for me, even though with the money I would have earned I would have been set for life”.

After the unhappy experience in Mexico came a new truce with Niculescu who called him back for the 1972 European Championship qualifiers.

Romania is in a group with Czechoslovakia, Wales and Finland. They arrive at the last two matches of the group, against Czechoslovakia and Wales with only one chance of qualification: to win both games.

In what would prove to be the decisive match against Czechoslovakia in Bucharest Dobrin scored the second and decisive goal to qualify his national team for the quarter-finals where they would have to concede to the Hungarians in the play-off in Belgrade on 17 May 1972.

Nicolae Dobrin will also be awarded in 1971 as the best Romanian footballer after his two wins in 1966 and 1967. Only three footballers in the history of this award have done better than him: Gheorghe Hagi with seven triumphs, Gheorghe ‘Gica’ Popescu with six and Adrian Mutu with four.

Finally, the funniest anecdote of all, also told by Viorel Kraus.

«A few hundred metres from our training ground in Ștefănești stood a church. The Orthodox ‘Pope’ was a huge Arges fan and in his Sunday morning sermon there was always a prayer for the team. He soon became friends with several of the team’s players… especially Nicolae Dobrin, who often escaped from training camp to spend Saturday nights drinking in the company of the priest, whose wine supplies were always plentiful!»

Many thanks to our friend Fabrizio Zaccarini, a great expert on Romanian football, for his valuable information on Dobrin and the Romanian football context of the period.