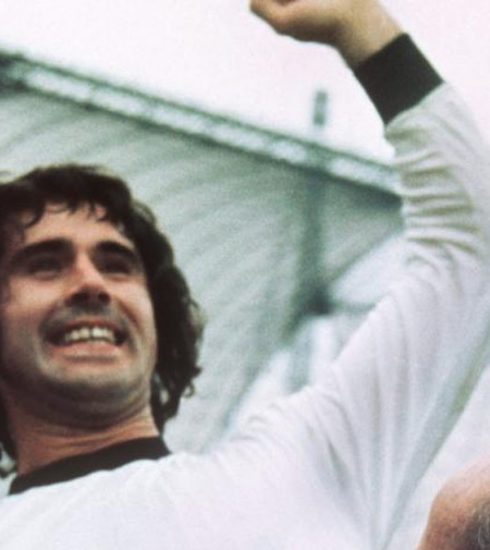

STAN CULLIS: Fuck them!

“Fuck them.”

These are the three words in reply.

They are uttered by a young English footballer, just 21 years old.

They are the words he uttered in front of the 14-man select committee of the England national team, just hours before taking the field in a prestigious international match.

“You do know, don’t you son, that at this point there will only be one place in the stands for you?”

Tom Whittaker, who is the one who leads the training sessions but has no bearing on the choice of formation, tells him.

“Fuck them.”

Is the reply, identical, from the young England Lions defender.

“Whatever you like. It will mean someone else will play in your place.”

But what could have happened to make an English footballer, and a very young one at that, decide to prefer the stands rather than a place among the starters in an important international match with the jersey of his country’s national team?

It is 1938.

For the English national team these are years of self-imposed football embargo.

Too proud (or haughty?) of their own footballing history as the inventors of the most beautiful game in the world to stoop to accept comparison with other nations in official competitions. Better to limit themselves to a few friendly matches, which are always well remunerated financially.

Even for the upcoming World Cup in France, the decision of the English Football Association was clear: ‘we will not participate’.

Not even when, with the celebrated ‘Anschluss’ only a couple of months earlier, Germany invaded Austria, annexing it to itself and effectively eliminating their former neighbours from the next World Cup for which the Austrians were duly entered.

The vacancy was offered to the English, who once again turned down the invitation.

An invitation, however, that they will not refuse for this match on Saturday 14 May where the English national team is about to face Germany.

In a few hours the two national teams will take the field at the Olympiastadion in Berlin (the one made famous by the Olympics two years earlier).

The Germans had already been under the totalitarian regime of Adolf Hitler’s National Socialist Party for five years and the Third Reich was at that time at the height of consensus among the Teutonic population also thanks to a fierce and hammering propaganda campaign.

This also includes the organisation of this prestigious friendly in which Hitler and his acolytes stake another important slice of their reputation, not only in the sporting sphere.

The two greatest European powers facing each other on a football pitch.

It is not, as is often the case, JUST a football match.

The German national team, under the leadership of Sepp Herberger, comes from a streak of 16 consecutive useful results and the preparation for this match is meticulous.

Two weeks of intense training in the Black Forest to arrive at the top for the encounter with the English masters.

In contrast, England have just finished their gruelling season and the team is full of young, high quality but relatively experienced players.

Captain of the Whites for that match will be Eddie Hapgood, the only one along with Arsenal team-mate Cliff Bastin to have more than 10 appearances to his credit in the national team.

A few hours before the match, however, comes a strange ‘invitation’ directly from the British Foreign Office to the British ambassador to Germany, Sir Neville Henderson.

As a form of respect towards the German hosts, the English eleven will have to respond compactly to the Nazi salute when the teams are presented on the pitch.

The news somewhat disconcerts the English managers, but the committee managing the selection has no choice but to communicate this ‘superior’ decision to their players in the pre-match meeting in the hotel where formation and tactics are decided.

The news is greeted with great surprise and there also seems to be a certain embarrassment on the faces of the British players.

But there is also absolute silence.

Breaking this silence is a young 21-year-old footballer who is already a pillar of Wolverhampton Wanderers and has already made a couple of appearances for the senior national team.

What he will say you already know.

Stan Cullis will not play that game.

He will play a few more with the England national team before the outbreak of World War II interrupts, at the age of 24, his career just when a footballer is about to reach his full mental and physical maturity.

England, in front of 105,000 spectators including Hermann Goering, Rudolf Hess and Joseph Goebbels, would win the match 6 goals to 3.

But Stan Cullis, unlike the British government, the leaders of the English federation and all his comrades on that expedition to Nazi Germany, will be the only one who can still look back on that day without shame.

ANECDOTES AND TRIVIA

Stan Cullis played practically his entire career for Wolverhampton Wanderers, so much so that the great Bill Shankly, his rival in so many battles on the pitch first and from the bench later, said ‘One day I saw Stan Cullis bleeding. I guarantee you … he had blood as yellow-gold as the Wolves’ jerseys.”

His leadership skills were so evident that when Cullis in the 1936-1937 season took over at the centre of defence from the legendary Bill Morris he also inherited, at only 21 years of age, the captain’s armband.

In the following two seasons Stan Cullis was instrumental in transforming the ‘Wolves’ into a team of the highest level.

For two seasons in a row they fought for the title but always finished second, behind Arsenal and Everton respectively.

This last season will be particularly bitter for Wolves of the West Midlands who will not only lose the championship in the final weeks of the tournament after having dominated for a good part of the tournament, but will also be defeated in the FA CUP final (against Portsmouth) becoming the third team in history to “get” the double horror, that is to say to finish second in the league and lose the Cup final.

The English First Division championship resumed in 1946. Seven seasons had passed. Seven seasons sacrificed to the war. But things, for Wolverhampton, have not changed at all.

The team is still of the highest level and, as they had done in the two seasons before the war, the ‘Wolves’ find themselves still fighting for the title.

Contending for it this time are the Liverpool Reds.

For Wolves and its passionate fans it is an extraordinary season.

They are all convinced that this is the right time: the title of champion of England, for the first time in its history, will end up in the hands of the yellow and gold from the West Midlands.

To make this epic championship finale even more epic, there is also the fact that the last game of the championship will see Wolverhampton and Liverpool face each other.

Wolves are one point ahead of the Merseyside Reds and have a better goal difference.

In short, two out of three useful results.

And what’s more, they play at Molineux, Wolverhampton’s den in front of almost 51,000 spectators.

Wolverhampton, however, were contracted, nervous and confused.

The fear of falling at the last hurdle again is evident.

Liverpool dominated the match in the first half.

It first took the lead through Balmer but the goal of the final knockout came a few minutes before the end of the first half.

There is a long rebound of the Liverpool goalkeeper Sidlow on which the number 9 of the Reds Stubbins ventures. He sprints towards the opponent’s goal.

Stan Cullis tackles him.

Stubbins touches the ball forward anticipating the Wolverhampton captain’s intervention by a whisker.

Little harm done.

It would be enough for Stan to get between the Liverpool striker and the ball, moving him just enough to throw him off balance.

A penalty almost 30 yards from goal and perhaps an official warning from the referee.

But Stan Cullis does none of this.

Stubbins sprinted past him, reached the ball and then thunderstruck Williams, the Wolves goalkeeper, with a sharp low shot.

It would prove to be the decisive goal, not only of the match but of the entire league.

In the second half Wolverhampton shortened the gap with Dunn but failed to score the equaliser.

There will be many who will reproach Cullis for his passivity in that play which, in fact, decided an entire season.

Some journalists at the end of the game will even dare to ask him why he did not resort to a foul in such a decisive action.

“Simple” was Stan Cullis’ reply.

“Because I don’t want to be remembered as the man who allowed the Wolves to win the first title in their history with a sportingly dishonest gesture.”

And in this sentence is REALLY all of Stan Cullis.

This will also be Stan Cullis’ last chance to win the title with his beloved Wolves.

In fact, at the beginning of the following season came a bad injury against Middlesbrough that, at only 30 years of age, would force him to retire from competitive activity.

At Wolverhampton Wanderers Football Club, however, everyone is well aware that Stan’s ‘football knowledge’ and charisma cannot be wasted.

And so exactly one year later, in June 1948, Stan Cullis became the new manager of Wolves, at only 31 years of age.

He will be the one to rewrite the history of this club, turning it into one of the strongest teams in England (winning three championships and two FA CUPs) and Europe for over a decade.

Yes, of Europe.

Because Stan Cullis will be so far-sighted and ‘forward’ to realise that the time has come for British clubs to break out of the absurd self-isolation they have always imposed on themselves.

And so at the Molinuex, one of the first English stadiums to be equipped with lighting for evening matches, some of the greatest European club teams took the field within a few years.

Famous in this respect was the match played against the great Honved of Ferenc Puskas, Sandor Kocsis and Zoltan Czibor.

The match was played on 13 December 1954.

Just over a year has passed since the great Hungary tore the English national team to shreds with a peremptory 6 to 3 on its hallowed ground at Wembley.

It was played at night and the second half, a first for the time, was broadcast live on the BBC.

When UK football fans got in front of the TV to watch the second 45 minutes, Honved was already ahead by two goals to nil, scored by Kocsis and Machos in the first quarter of an hour.

What they did not get to see was an authentic display of football by the Hungarians, whose creativity, technique and organisation of play was unmatched by the albeit very strong English team.

In the second half, many people logged on to admire the exploits of the great Hungarian champions. What they could not expect, however, was a second half dominated in a clear and authoritative manner by the yellow-golds, who first shortened the distances with a penalty kick by Hancocks and then completed the comeback with two goals in three minutes by centre forward Swinbourne.

But what happened? How was such a transformation possible?

Stan Cullis realised at half-time that there was no match like that, and that continuing in this way there was a risk of a worse defeat than the one the national team had suffered at Wembley the year before.

There are two moves: the first is to bypass their midfield with long throws towards the four strikers (two central and two outside) thus bypassing the very strong Hungarian midline.

The second is even more concrete: Cullis instructs the caretakers, ball boys and youth players to literally drench the pitch with water, so as to mitigate the great technical gap between the two teams.

An account confirmed by Ron Atkinson, a great English coach of the 1980s and 1990s (WBA, Manchester United and Aston Villa among others) who on that day participated with several youth teammates in the ‘bog’ operation at half-time of the match.

One of the millions of spectators in the United Kingdom who watched that match, eventually making him fall in love with Wolverhampton, was an eight-year-old boy from Belfast, Northern Ireland.

His name was George Best.

Finally, no one could sum up Stan Cullis in a thought better than the great Bill Shankly.

«Although Stan could be very irascible and sometimes even outrageous, he was a very good-natured and generous person. One of those people who would give his last penny to a friend. He loved Wolves, he would have given his life for them, but most of all he was a person of well above average intelligence who would have succeeded in whatever he chose to do. Since football was invented I am hard pressed to think of a better person than him».

Stan Cullis, the man who refused to bow down to the Nazis.