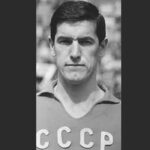

VALERIJ VORONIN: A life broken in two

The 1966 World Cup has just ended. England, on friendly soil, has won its first title.

It is time for the award ceremony and among the usual prizes, individual and team, there is a special one, never before instituted.

Personally presenting it to the winner is none other than Queen Elizabeth.

It is a silver porcelain service that the young sovereign hands over to a young Russian footballer.

The motivation? The most ‘elegant’ footballer in the entire tournament.

The name of this footballer is Valerij Voronin, he is Russian and is much more than a charming young man.

Valery Voronin was born in Moscow in July 1939.

His is a wealthy family. His father runs an important food warehouse, which in the USSR, during the war and post-war period, guaranteed important ‘revenues’ and contacts with the highest spheres of society in the country.

The family business is located in Peredelkino, in the south-west of the city and known as the artists’ quarter.

Valerij is soon completely absorbed in that environment. He avidly reads the Russian classics but is very attentive to the new frontier of his country’s literature, which soon becomes targeted by the central power.

Voronin forged deep friendships with many intellectuals of the time, first and foremost the Nobel Prize winner Boris Pasternak and poets such as Andrei Voznesensky and Yevgeny Yevtushenko.

In his adolescence, in addition to his passion for art (he also became a lover of Jazz, one of the disciplines most disliked by the central power), he discovered, however, that he had a particular talent for a discipline that, finally cleared through customs by Stalin only a few years earlier, was becoming increasingly popular in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics: football.

At the age of sixteen, Valerij entered the prestigious FShM, the football school of excellence in the USSR and which trained footballers of the level of Vladimir Fedotov and Igor Chislenko among others.

Voronin has an athletic physique, exceeding one hundred and eighty centimetres in height, but it is in his technique and vision of the game that he has the best gifts.

He already has a declared idol, even though he is only two years younger than him.

He is Eduard Streltsov, a pure talent and unanimously considered ‘the strongest Russian field player’ … given that Russia has a certain Lev Yascine between the posts …

But it is not only his footballing qualities that make him so fascinating in the eyes of the young Voronin. Streltsov is an ‘outsider’, someone with a strong personality and very little in the way of a power system that demands efficient little soldiers loyal to the dictates of the Party.

Streltsov loves women, vodka, nightlife and is certainly not the best example for Russian youth.

Voronin meanwhile becomes one of the most sought-after youngsters in Russian football, and when at the age of eighteen he receives an offer from Torpedo Moscow, the team where Streltsov plays, for him there is not a doubt in the world: Torpedo will be his team.

And it matters little if in the Russian capital it is the poor relation of such teams as Dinamo, CSKA and Spartak.

Playing with Streltsov is a dream come true for Voronin … even if it lasts only a very short time.

In that 1958 Streltsov is jailed on charges of rape.

He will miss the World Cup in Sweden that same year.

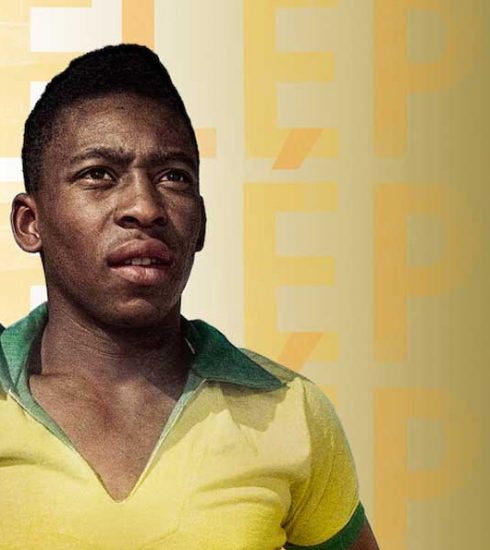

Those in which Pelé’s talent will blossom and in which two of the greatest promises of world football at the time will not be able to participate: Streltsov, locked up in a Gulag, and Duncan Edwards, who died a few months before the Munich air disaster with his Manchester United team.

In the economy of the Torpedo game it is Voronin who takes Streltsov’s place. Not so much as a position on the pitch (Voronin is a defensive midfielder), but above all as a figure of reference due to his leadership skills, tactical intelligence and considerable physical strength.

In 1960 for the ‘little’ Torpedo came the championship triumph.

A result that was as unexpected as it was deserved and in defiance of the themes of central power (CSKA and Dinamo above all).

In that same year Voronin made his debut in the national team and soon became an indispensable starter for eight seasons, participating in the 1962 and 1966 World Cups, standing out in both events and being judged as one of the most valuable and complete midfielders ever.

These were wonderful years for Voronin.

In addition to his fame as a sportsman, there is a great personal charm that makes him the object of the attention of the female public in his country and beyond.

He lives these years with great intensity and even though his personal interests and friendships put him at the centre of attention of the notorious KGB Voronin continues to play football and become increasingly popular with the public and the media.

Added to this is the return of his idol Eduard Streltsov.

Released from prison in 1963, he finally receives permission from the new General Secretary of the Russian Communist Party Leonid Brezhnev to return to football.

The results are immediate.

Torpedo Moscow wins the championship again, five years later.

Streltsov, although weighed down and debilitated by the five terrible years in the Butyrka gulag, is still a fine footballer.

“Running for him is also a pleasure and an honour. I will proudly tell my children and grandchildren that I played and won a championship alongside Eduard Streltsov,’ Voronin will say with pride and great humility at the end of that triumphant season.

After the excellent World Cup played in England, which saw the USSR arrive for the first time among the four best football nations in the world, the next appointment was the 1968 European Championships, whose final phase was played in Italy.

Voronin was among those called up, but some disciplinary problems made him fall out of favour with the national team’s technical director Mikhail Yakuschin and so Voronin did not take the field either against Italy (in the famous semi-final decided by the coin) or in the ‘final’ for third and fourth place against England.

Much more serious was to happen a few weeks later.

In that summer Voronin was the victim of a serious car accident from which he was miraculously saved. His perseverance will also allow him to return to the pitch with his Torpedo the following year.

But it is clear that Valery Voronin is not what he used to be.

He has lost physicality and lucidity in his game.

Moreover, the accident left several marks on the face and body of the man who was nicknamed ‘the Russian Alain Delon’ due to his attractiveness and charm for the fairer sex.

He gave up football and at this point a sad parable of bad friendships, depression and much, much alcohol began for him.

His life will end in May 1984 when Voronin is not yet 45 years old.

His body will be found in the bushes just outside Moscow with his skull smashed in.

No one will ever be charged or arrested for his death.

ANECDOTES AND CURIOSITIES

Voronin’s interests in the West (including texts by British and American writers) and his friendships with various footballers on the other side of the wall (George Best, Bobby Charlton and Pelé) put him at the centre of the KGB’s attention for years. The KGB closely monitored Voronin’s movements at a time in the post-Stalin USSR when myths such as Gagarin, Yascine and Valerij Brumel were presented as examples of the new Russian society.

The 1962 World Cup in Chile was Voronin’s first major international showcase.

The USSR was fresh from the victorious European Championships won in France two years earlier and arrived at the World Cup with high expectations.

The group is easily won but in the quarter-finals it falls to hosts Chile. Valerij Voronin, however, was included in the ‘all-star’ line-up of the event at the centre of a defence that also included Cesare Maldini, Djalma Santos and Karl-Heinz Schnellinger.

At the 1964 European Championships, the USSR finished in second place, narrowly losing the final to hosts Spain. The Soviets had a great squad. Yascine in goal, Voronin in midfield and in attack the lethal Ivanov, top scorer at both the 1960 European Championships and the 1962 World Cup in Chile.

At the end of those European Championships, Valerij Voronin was the only one not to forget Streltsov, who had been released from prison a few months earlier. ‘I don’t know where we would have got with Eduard in the team too,’ he told the press at the end of the event.

In that same year, as mentioned, it will be the new Communist Party secretary Leonid Brezhnev who will remove Streltsov’s lifetime disqualification from professional football.

In those years Voronin was probably at the peak of his career. At the end of both 1964 and 1965 he was voted ‘Best Footballer in the League’ and the following year, at the English World Cup, came the definitive consecration for him.

The USSR flew into the qualifying round.

Three wins out of three against North Korea (who would resoundingly eliminate the Azzurri) the Italian national team and Chile.

In the quarter-finals, the Soviets fell to Hungary in whose ranks played the great Florian Albert (who would win the Golden Ball the following year).

USSR coach Nikolay Morozov was well aware that limiting Albert’s influence in the match could prove decisive.

Voronin, who until then had played as a midfielder, is asked to personally take over the marking of the talented Hungarian footballer.

It will be the winning move.

Voronin will play a sumptuous game, once again demonstrating his great eclectic skills.

The USSR will fall in the semi-finals under the blows of West Germany, but will place among the four strongest football nations in the world for the first time.

Upon returning home, Voronin became a star.

He has a beautiful wife and the couple is invited to all the social receptions and parties in the capital.

Voronin begins to lose his bearings and his passion for the bottle, never hidden, becomes more and more constant.

This brings us to that summer day in 1968.

Voronin is on a retreat with the national team, but the previous evening he has not respected the rules imposed on the team’s players by returning to the hotel well after the permitted time.

Disciplinary action was taken against him and he was expelled from the retreat.

Just as he was driving home, he lost control of his car and drove into the oncoming lane, colliding head-on with a heavy goods vehicle.

One of Voronin’s best friends in the last tragic period of his life was the actor, poet and singer Vladimir Visotsky. A true ‘accursed genius’ of the Moscow cultural scene and always known for his alcohol and drug abuse.

Several attempts were made by Voronin’s former teammates to bring him back on the tracks of a less transgressive and destructive lifestyle, but it was all to no avail.

One of the closest to Voronin was one of his coaches at Torpedo, Yuriy Stepanenko.

He was one of the most assiduous in trying to save Voronin from the self-destructive spiral he had entered.

And he was the last friend to see him alive.

“I saw him the day before his death. He was in the company of three very unsavoury characters. I told Valerij that those were not the kind of people for him. He had one of his bitter laughs and then got into the car with them. The next day his body was found near Varshavkoe Shosse with his head smashed in’.

Finally, some data that can help define the prowess of this almost unknown champion.

In the Ballon d’Or ranking Valery Voronin ranked 10th in 1964, 8th in 1965 and 11th in 1966 … not bad for an ‘unknown’.

Author’s note:

This piece was written drawing from various journalistic sources, most of them English. One of these sources, however, is very Italian and is the tribute to Voronin written by my friend Simone Cola in his beautiful blog “Uomo nel pallone” from which I have drawn several invaluable pieces of information. Thank you Simone.