DANIEL PASSARELLA: The great captain

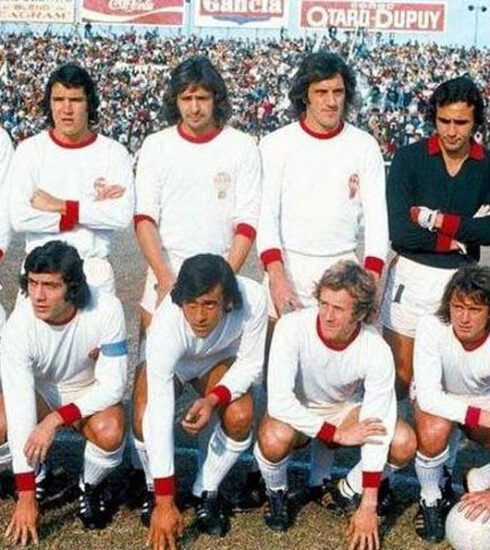

When the legendary Guerin Sportivo began to talk about the upcoming 1978 World Cup in Argentina, one of the players most frequently mentioned was this River Plate defender, with a career and statistics all of his own. From the Argentine Serie C to the national team in less than three years and with a score between appearances and goals that made one think of an offensive midfielder or a winger rather than a central defender. When, after so much praise for this player, a true leader of the biancocelesti, I saw his photo in the Guerin Sportivo with the Argentine national team jersey, it was ‘love’ at first sight: Passarella was the first one standing on the left, captain’s armband, (recently inherited from Carrascosa, another wonderful story of which you can read here on Calciomercato), old-fashioned tough face and four good fingers taller than all those in the photo!

I needed a couple of matches where, while admiring his incredible leadership skills, a terrifying left foot and above all an absolutely crazy elevation, I had the doubt that Passarella wasn’t so tall … and in fact I soon discovered that not only was he 174 centimetres tall but that in all official photos he stood strictly on tiptoe, thus appearing at least 10 cm taller!

In the World Cup in Argentina he was a real dragger. Excellent in organising the defence, tough to the limits of the penal in confrontations, very good at getting the action going whether it was by coming out of defence with his foot or with millimetric throws of over 40 metres. Lethal in free kicks and from the penalty spot he was virtually ‘unmarkable’ in aerial play. He had an absolutely insane elevation, NBA or high jump platform.

Seeing him carried off in triumph at the end of that World Cup with the Cup in his hands was a great satisfaction for a young boy like me, who had never denied that I shamelessly supported the biancocelesti in that World Cup, essentially because of the presence of PASSARELLA in that excellent team.

I only learned several years later in what context those World Cups were won, with a country crushed by one of the bloodiest dictatorships of the 20th century.

For Passarella, his arrival at the football that counts was certainly not all sunshine and roses.

Far from it.

If you are born in Chacabuco, more than 200 km from Buenos Aires, the opportunities to make a name for yourself are not the same as for a kid from the capital, where practically every neighbourhood has a professional football team. However, his grit, even more admirable when combined with his small stature, and his skill in the aerial game from a young age, does not go unnoticed by the capital’s big clubs. First Boca Juniors, then Independiente and finally Estudiantes offered the determined little Indian-faced boy a try-out, but things, for one reason or another, did not go as hoped.

Despite these three burning failures, Daniel does not lose heart. Certainly not him who, as a child, first broke his leg in a car accident together with his maternal grandfather (and for this reason he forced himself to learn to play with his left leg, the healthy one, so much so that he became a pure left-hander) or when he received a blow to the head in a match that made him think the worst … only to return to the field the following week!

For him came the call from Sarmiento, a small Serie C team where, however, Daniel took no time at all to impose himself as the absolute promise of Argentine football. It was the great Omar Sivori who, receiving enthusiastic reviews about that little full-back (yes, because at that time Passarella, after a start on the wing, played left-back) and especially after seeing him in action in a friendly against the Argentine national team of which ‘El Cabezon’ was then the manager, decided to warmly recommend him to ‘his’ River Plate where Passarella imposed himself at lightning speed. He was soon given the number 6 shirt, the one assigned to the libero. Passarella, after a short period of adaptation, began to do what he did best: organise the defence with his proverbial shouts or with reprimands, anything but polite, to teammates guilty of not applying themselves fully to the cause as he demanded. There were quite a few who found it a little difficult at first to accept that a young boy, much younger than many of his teammates, allowed himself to guide and scold assiduously, in matches as well as in training, older and already established teammates.

But it took very little to realise that Passarella’s was not just haughtiness or arrogance, but true and undisputed leadership qualities, which a couple of seasons later were even recognised in the national team of ‘Flaco’ Menotti, which was preparing to conquer the first World Cup in the history of Argentine football.

Once the triumphantly won World Cup was over, the flattery of European clubs was not long in coming. It was mainly Spanish clubs, with Real Madrid in the lead, that demanded Passarella’s services. But ‘El caudillo’ loved River and the fans and managers loved him. Passarella stayed at River, which, at least until 1981, was one of the greatest teams not only in South America but in the whole world, full of champions of the calibre of Luque, Fillol, Tarantini and the very young Ramon Diaz. Also because on the horizon was the World Cup in Spain, where the Argentine team set off with the well-founded hope of repeating the splendour of four years earlier. Yes, because an already strong and even more experienced team had been joined by a 21-year-old kid named Diego Armando Maradona. Things certainly did not go as planned and although Argentina did not demerit in either match of the second round, they were defeated first by Rossi & co.’s Italy and then by Brazil’s big stars Zico, Socrates and Falcao.

At that point, aged 29, Passarella decided to cross the ocean. Winning the battle to obtain his services is a club that is not top-notch, but ambitious and, above all, showered with money from the Pontello family: Fiorentina.

The start, however, is anything but easy. Italian football was different from the Argentine one, the relationship with the Pontellos was not idyllic from the start and Fiorentina’s coach at the time, De Sisti, wanted to limit both his sphere of footballing influence (no offensive raids but traditional free running behind all his teammates) and his personal influence (‘you are one of many, here the only one in charge is me’). Passarella, however, does not give up, and despite a difficult start, even with the fans who do not recognise the champion he admired with the Argentine national team, he adapts to do what the coach requires, limiting himself to giving his contribution in the offensive phase only on set pieces. However, this sense of self-sacrifice, this immense grit in wanting to give his contribution despite ‘self-castrating’ some of his best qualities, convinced even the most sceptical and Passarella played three more seasons at a very high level, in the last of which he scored a whopping 11 goals, him a ‘pure’ libero. At the end of the season, perhaps his best in the purple, Fiorentina and the Pontellos decided to disregard him, more for financial and personal reasons than technical ones, and so came the call from Trap’s Inter where Passarella played two seasons without ever expressing himself at more than a decent level. These seasons at Inter are unfortunately also remembered for an ugly episode in which his ‘sangre caliente’ and lack of self-control in the most heated agonistic moments, unfortunately reached a climax; during an Inter game in Genoa against Sampdoria, with Inter down by a goal, a ball boy was late in handing over the ball to Passarella for the throw-in. Passarella, unnerved by the boy’s attitude, kicks him. (Obviously an uproar breaks out in all the media, Passarella is branded as a brutal and violent ogre, and despite Passarella’s repeated reprimands and apologies, his image is inevitably tarnished. Passarella returned to Argentina, ended his career at his beloved River Plate and then embarked on a coaching career, with varying success, touring the world for several years, also leading Argentina to the 1998 World Cup and then Uruguay’s national team to the 2002 World Cup. In 2006 he returned to his beloved River and then took on the role of Club President from 2009 to 2014.

Here too he gave yet another demonstration of an almost indomitable strength of character: during his ‘reign’ the Millionarios suffered the shame of relegation in 2011. Passarella lived through hellish months, amid death threats, insults and insults at all levels. He did not give up: he remained at the top of the club, taking it, together with the talented Matias Almeyda as coach, back to the top flight. In the following season he even reached the title with his friend Ramon Diaz on the bench.

The last ‘gift’ of the much disputed Passarella to his beloved ‘Millionarios’ is probably the most important of all: it is precisely ‘El Caudillo’ who in June 2014, in place of the resigning Ramon Diaz, convinces the young Marcelo Gallardo, former great midfielder of the club but with only a brief experience in Uruguay as coach, to sit on the River Plate bench. Here too there was endless controversy and discussion over the choice of Passarella, especially by those who considered ‘El Muñeco’ still too immature for such a responsibility.

… Within a few seasons Marcelo Gallardo would become the most important and successful coach in the club’s history.

ANECDOTES AND CURIOSITIES

Like everyone in his family, ‘El Mocho’ (this was Passarella’s nickname as a child) was an ardent ‘hincha’ of Boca Juniors and Angel Clemente Rojas known as ‘Rojitas’ was his great idol.

It was at Boca, where he dreamed of playing, that Passarella had to accept one of the greatest humiliations of his career.

In 1970, overcoming competition from several Argentine clubs, Boca Juniors offered Passarella the chance to join the youth sector.

He was a guest for almost three months in the club’s sports citadel, the famous ‘Candela’.

Youth sector manager Bernardo Gandulla tells him that he can leave his job as a worker in Chacabuco and consider himself a Boca player.

A few days later a certain Campos arrives as the new coach of Boca’s junior team … who after a couple of training sessions lets the club know that he doesn’t need Daniel Passarella.

No contract had yet been signed and Passarella had to return to Chacabuco with his tail between his legs … and a hatred, which never subsided, towards Boca Juniors.

Nothing seems to go right in those years. Frustrations follow one another without interruption.

The following year, in 1971, it is Independiente who offer him a trial period. Passarella is used as a central midfielder. The coach, ‘El Pipo’ Ferreiro, is enthusiastic. He informs Daniel’s father that he will be offered a contract.

When all the documents are finally ready, they realise that the transfer deadline has closed.

The transfer ‘skips’.

With Estudiantes the following year, history repeats itself. Three months on trial, everything ready to sign when a half revolution arrives at the club. Half the management and almost all the technical staff are replaced, including ‘El Cochero’ Antonio, who had expressly asked for Passarella.

Third sad return to Chacabuco …

Even for someone as ‘tough’ and determined as Passarella, this time is just too much. ‘Enough. I don’t audition any more. I’m staying in Chacabuco and whoever wants me will come here to buy me.

It is his father who convinces ‘El Mocho’ not to give up.

“Son, the good ones always emerge sooner or later. Your turn will come too’.

All true. In 1973, when Passarella was already twenty years old, it was a small club, Sarmiento de Junin, which played in the Primera C (the third division of the Argentine league) that signed him.

After several months warming the bench under the direction of Coach Villafane at the Club comes ‘El Tucumano’ Hernandez. He immediately inserted him into the team as left-back. Passarella ‘explodes’. He played at a very high level, became irreplaceable at the Club and even ended the season with 15 goals as his personal haul.

Also in 1973, while Passarella was a player at Sarmiento, the turning point came. In Junin, a town in the province of Buenos Aires located on the banks of the Salado del Sur river, the Argentine national team, led at the time by ‘Cabezon’ Omar Sivori, arrived for a friendly match.

The day before the match the Argentine national team’s left-back Antonio Rosl was injured and Passarella was asked to play in his place with the Argentine national team.

For everyone it would be considered a golden opportunity.

Not for Passarella.

‘No. I will play for my team, Sarmiento de Junin. I’m not interested in playing with the national team. If I had to play a good game, everyone would say it would only be because I play among the best players in the country.”

A half case ensues, but Passarella does not give up.

The next day he took to the field with Sarmiento, in the ‘cancha’ he was one of the best playing in marking the great Boca striker Ramon ‘Mané’ Ponce and inevitably attracting the attention of Sivori himself, who strongly advised River Plate coach ‘Pipo’ Rossi to buy the awful, stubborn kid.

A few weeks later Daniel Alberto Passarella left Chacabuco for Buenos Aires … this time never to return.

It is in the famous ‘Torneo del Verano’ at the beginning of 1974 that Nestor Rossi intends to make young Passarella’s debut.

Not just any match, but in the ‘Superclasico’ of Argentine football: against Boca Juniors.

The dialogue between the two is in River Plate history.

“Son, do you feel up to playing in such an important match?” the coach asks Passarella.

“Forgive me coach. I feel very much like it ! … the question is whether you feel like putting me on the field,’ is Passarella’s brilliant reply.

At River Plate Passarella would probably play the best years of his career, winning 7 national titles and being the only player in the history of Argentine football to have won both ‘World Champion’ titles, having been part of the squad both in 1978 (where he revealed himself to the world as one of the best defenders on the planet) and also in 1986 where due to physical troubles he still could not play a single minute.

There is no doubt what the highlight of Daniel Alberto Passarella’s career was: winning the 1978 World Cup title with his Argentina team in the World Cup organised in the country during Videla’s bloody dictatorship.

It was Passarella himself, as captain, who raised the trophy to the sky on that night in Buenos Aires.

The story of that captain’s armband left vacant by ‘Lobo’ Carrascosa, Cesar Menotti’s authentic right-hand man in Huracan first and in the Argentine national team later, is one of the most debated in the history of Argentine football.

The fact is that to the surprise of many, Cesar Menotti elected the then 24-year-old Passarella as captain of his national team.

‘El gran capitan’ never disappointed and it was his leadership skills that impressed the observers during that World Cup.

At the end of the 1982 World Cup, which ended with the elimination in the second round thanks to Bearzot’s Azzurri, the Argentine federation decided on a radical change: in place of Cesar Menotti, convinced offensive player and faithful to the purest tradition of Argentine football, made of creativity and technique, came Carlos Bilardo, ‘godson’ of Osvaldo Zubeldia, famous manager of Estudiantes, who made physical preparation and defensive organisation (and a hard and intimidating game) his absolute dogmas.

The first thing Bilardo does is remove Passarella’s captain’s armband to hand it over to the undisputed ‘crack’ of world football: Diego Armando Maradona.

Taking away his armband is one thing, taking him out of the starting eleven (as Dieguito would like) is another.

Especially when, in the decisive match for qualification for the Mexican World Cup against Peru, it was Passarella who provided Ricardo Gareca with the splendid assist for the decisive goal.

… The ‘revenge of Montezuma’ and some strange political games will, however, take away Passarella’s chance of winning his second World Cup on the field.

To close, a figure that perhaps tells the greatness of this central defender better than many words.

This is Daniel Alberto Passarella’s career tally: 175 goals scored in 611 official matches.

… a figure that would make many strikers happy …