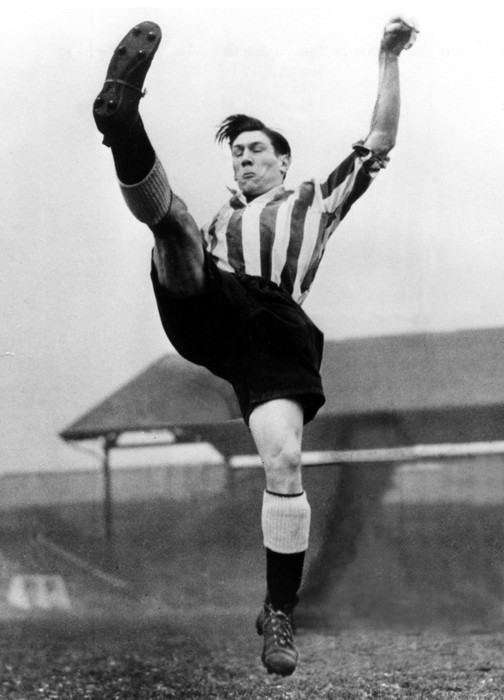

LEN SHAKLETON: The first true ‘maverick’

“The Clown Prince of football.

That’s what they used to call me when I played.

Prince and clown.

I was exactly that.

A prince because of my elegance, the speed of my movements, my class … and also because of all the money I was worth!

In 1948 Sunderland Football Club paid over £20,000 for my tag. A world record at the time.

And I was also a clown.

How I loved to entertain and amuse!

I always thought that people who came to the stadium, spending their hard-earned money in the mines or the steelworks, deserved more than a nice goal, a successful dribble or a good save.

And so I invented something different every time to get a laugh out of all these people.

Like, for example, dribbling past an opponent and before another one came underneath, stopping and fixing my hair.

Or leaving a defender from the other team on the spot, stopping and looking at an imaginary wristwatch.

How pissed off the opponents were!

One day against Arsenal, after one of these tricks, one of their defenders came at me with all his strength at knee height… only I was too quick and agile for him!

So I jumped as high as I could. I avoided the impact and he ended up lying on the Highbury turf … with his fans laughing their heads off!

My favourite little game, however, was another: the ‘give and go’ with the corner flag.

It had become my speciality.

I would go with the ball near the corner flag and wait for an opposing defender to arrive, and then I would kick the ball against the flag, outflank the unfortunate defender, and go and get the ball back.

The stadium would come down!

… to tell the truth, sometimes the trick didn’t work for me and the ball would sadly end up over the goal line.

This time it was my coach and my teammates who were pissed off.

Well, as they say … not all the donuts come with the hole …

But that’s me. Take it or leave it.

And then … after you’ve just come out of a war or had to work in a mine what does winning or losing matter?

Having fun and enjoying yourself is what counts.

Besides, if I don’t have fun, how can I expect those who come to watch the games to have fun?”

Len Shakleton was in all probability the first true ‘maverick’ in the history of British football.

That sort of slightly mad ‘entertainer’ who loved playing football without ever losing sight of the joy … in their plays and for those who came to watch them from the stands.

A left halfback or winger, a player of pure talent, gifted with technique, dribbling, speed and a great shot that allowed him to score 127 goals in 384 league games with Newcastle and especially with Sunderland, the team in which he played for nine seasons and of which he is still one of the absolute icons.

It was in the old and atmospheric Roker Park, the ‘Black Cats’ stadium, that Shakleton gave his best and became a legend of the club.

Leonard Francis Shakleton was born in Bradford, Yorkshire, on 3 May 1922.

It was immediately obvious that his talent with a ball between his feet was out of the ordinary.

When he was called up for the England Under-14s (England Schoolboys) he became the first Bradford-born footballer to have this honour.

On his debut against Wales’ peers he scored a brace in the six-two final for England.

It is at this point that Arsenal manager George Allison arrives from London and convinces the young Shakleton to follow him to London.

After not even a year in the capital it is Allison himself who gives him what seems to be a life sentence: ‘You are too small and fragile to play football. Give it up son. You’d better look for a real job’. After a few months in London without finding any signings Shakleton returned to Bradford. Welcoming him is his old team, Bradford Park Avenue, basically the city’s second team.

However, the world conflict is just around the corner.

Shakleton manages to stay in the area working as a radio builder for military aircraft and continuing to play football for Bradford.

When the war ended in the 1946-1947 season he resumed his official activities.

He played seven games (and scored four goals) with Bradford Park Avenue when in October 1946 the ambitious Newcastle, a team desperately struggling to get back into the First Division, came forward.

For Shakleton the ‘Magpies’ spend a whopping £13,000, exactly what Liverpool received for the transfer of Albert Stubbins.

On his debut at St. James’ Park against Newport County Shakleton would score six goals in the thirteen-nil triumph … Newcastle’s unbeaten record for goals in a game.

What seems like an idyll soon turns into a nightmare. Despite the wonderful relationship with the fans who love his plays, relations with the management soon became strained.

In his first season in ‘Geordie Nation’, promotion does not come. There is a disappointing fifth place only partially compensated by a splendid march in the FA CUP that will however end in the semi-final against Charlton.

At the end of this match Shakleton and captain Joe Harvey announce that they will no longer play for the club until the promise of a home for both of them made by the management at the time of their signing is fulfilled.

The management is forced to relent but relations with Shakleton have finally broken down.

When then, in December 1947, Shackleton refused to join staff and team-mates on a mission to London to ‘study’ future opponents in the FA CUP (Charlton Athletic) the situation became untenable.

Shakleton will ask to be put on the club’s ‘transferable’ list.

He will be accommodated.

A few days later it will be Sunderland, Newcastle’s historic rival, who will come up with the pharaonic sum of £20,500 to wrest the talented midfielder from their rivals.

It is February 1948.

With the Sunderland fans it will be love at first sight and this time destined to last.

The beginnings are actually anything but easy.

Sunderland will spend an impressive sum in an attempt to build a team capable of winning the title: £250,000. ‘The Bank of England’ will be their nickname in that period.

Things, however, did not go as planned.

At the end of that season Sunderland would finish third last, just four points ahead of Blackburn Rovers, one of the two teams relegated to the Second Division.

“We were excellent individuals but we weren’t a team,” said Shackleton of his first spell at Sunderland.

Slowly, however, the team began to amalgamate and the results were the direct consequence.

The coveted title, however, will never come at Roker Park in Sunderland.

There will be brilliant seasons like the one in 1949-1950 where the ‘Black Cats’ will finish in third place just one point behind champion Portsmouth or the fourth place in 1954-1955 just four points behind Chelsea.

Even in the FA CUP Len Shackleton will end his career without a title and without even managing to step onto the Wembley turf for a final.

Sunderland would fall twice in the semi-finals.

In 1955 at the hands of Manchester City and the following season with a clear nil to three against Birmingham.

It’s the 24th of August 1957. The first league match is being played. Len Shackleton suffers a serious ankle injury during the match.

Shackleton will never return to the pitch for an official match.

His importance in the team was soon realised by everyone … at the end of the season for Sunderland came a bitter and unexpected relegation.

At the age of 35 Len Shackleton will end his career.

A career where he certainly reaped far less than his talent would have deserved. No titles, no medals and the pittance of five ‘caps’, the caps that the English federation gave to its players for each appearance in the national team.

But ‘winning’ in a different, perhaps even more important way: having made the fans fall in love with him, having entertained them with his plays and made them smile with his jokes.

ANECDOTES AND CURIOSITIES

In order to avoid being called up for military service in 1945 and thus miss the start of the first post-war championship scheduled for the following year, Shackleton agreed to become one of the famous ‘Bevin Boys’, those boys who, in order to help the country in the serious energy situation of the immediate post-war period, opted to go into the coal mines, thus avoiding military service. Bevin was the Labour minister at the time who had had this insight.

It was also thanks to this experience, which Shackleton described as ‘terrifying and exhausting’, that he became aware of how important it was to give something extra to the football fans in the stands after a week of hard work in those poor conditions.

With the war and mining experience over, Shackleton returned to the ranks of Bradford Park Avenue in the 1946-1947 season. It would be seven appearances in all (and four goals) before Newcastle came to the club’s management with a hefty cheque for £13,000.

Shackleton will leave, as he almost always does, with the usual bitterness and controversy.

‘I was tired of playing for such an incompetent public’. Shackleton’s individualistic style, always looking for ‘the play’, was not particularly appreciated by the local fans who accused him of falling a little too much in love with the ball and being impractical.

“If I do it is because I am waiting to find the best option. But to explain it to people who understand nothing about football is virtually impossible,’ Shackleton would later say of that time at Bradford P.A.

The English national team chapter is one of the most controversial in Len Shackleton’s career.

It could be said that his fate was identical to that of the ‘Mavericks’ who arrived on the English football scene some twenty years later. Charlie George, Stan Bowles, Rodney Marsh, Alan Hudson, Frank Worthington … all players who despite their unquestionable talent put together little more than a handful of games with the national team of the Lions of England.

In fact, Shackleton played the pittance of five games, some of them objectively anonymous, but with a great satisfaction in the last of them.

It is the first of December 1954. At Wembley came West Germany, who had become world champions the previous summer after defeating the great Hungary of Puskas, Kocsis and Hidegkuti in the final in Bern. England won by three goals to one and Shackleton played an extraordinary game, sealed by a beautifully crafted goal: he ran into the area with his foot and lobbed a shot past the German goalkeeper Herkenrath.

“It was the goal that gave me the most satisfaction. Not only because of the prestige of the match but because I did exactly what I had planned to do even before the ball got between my feet,’ Shackleton recounted in his biography.

During his early years at Sunderland Shackleton was at the centre of a long dispute with ‘Black Cats’ centre forward Trevor Ford.

The latter complains about Shackleton’s selfishness in wasting himself in pointless ‘squiggles’ instead of passing him the ball. In his biography Ford writes that ‘there were countless occasions when we could have scored but with Shackleton slowing the game down we gave the opposing defence time to regroup’.

Things got so bad that Ford himself went before team manager Bill Murray and said he would never play another game where Shackleton was on the field.

… Trevor Ford was traded to Cardiff in November 1953 …

The story goes that at the most tense moment between the two Shackleton was capable of serving seemingly inviting balls to his own number 9 … only, laden with effect, as they touched the ground they slipped out of Ford’s control and he ended up looking terrible.

Amongst the many follies enacted on the football pitch by Shackleton, what the talented Bradford midfielder pulled off in a match between Sunderland and Manchester City in August 1951 stands out.

The Black Cats were awarded a penalty kick.

The shot was taken by Shackleton himself.

He places the ball on the penalty spot and starts to back away for the classic run-in.

Back … back … back … back … when he stops he is a few metres from the halfway line.

When the referee blows his whistle Shackleton sprints full speed towards the ball … which he pretends to hit but doesn’t even touch.

Bert Trautmann, the legendary City goalkeeper, dived to his left.

At this point Shackleton turns and backheels the ball into the unguarded goal on the opposite side …

“The rest of the game I spent saving my legs from being kicked by the Manchester City defenders who, in short … didn’t take it very well!” Shackleton would recount with his usual irony a few years later.

There were also several problems with the Sunderland management at the end of his career.

Shackleton, who played nine seasons with the Wearsiders, asked the club to organise a ‘Testimonial Match’ in his honour, which is nothing more than a farewell match for a footballer recognised as a reward for his long militancy with a club. A large part of the proceeds from this type of match ends up in the player’s own pocket … a kind of severance pay at the end of his career.

Normally this important award was organised for players with at least ten seasons at a club.

Sunderland, inflexible, pointed out to Shackleton that the seasons he had played were not enough. Shackleton, for his part, reminds his managers that he would have made it to ten years of militancy had it not been for that ankle injury that in the first game of the tenth season ended his career … playing for Sunderland Football Club!

We are “at the impasse”.

At this point Shackleton plays his trump card: he threatens the management to report to the English Federation some ‘off the books’ payments made by his managers.

The situation is unblocked in no time and so Shackleton gets his (well-deserved) farewell match.

The match was played on 15 April 1959. “Sunderland vs Shackleton All Star XI”. It was played, of course, at Roker Park where Sunderland won by five goals to four.

In the ranks of the ‘All Star XI’ fielded by Shackleton (who would only play the first forty-five minutes of the match) there were top footballers such as Jackie Milburn, Johnny Haynes and Tommy Docherty … and alongside them also Brian Clough and Don Revie, sworn enemies some fifteen years later!

Nearly 27,000 spectators attended the match, which contributed in no small part to lining the pockets of Len Shackleton, the ‘Clown Prince’ of English football.

Towards the end of his career, Len Shackleton published an autobiography entitled ‘The Clown Prince of Soccer’, which sold like hot cakes to the extent that it was reprinted five times in just three months!

One of the chapters of this autobiography is entitled “How much do football directors know about football”.

… the page is completely blank …