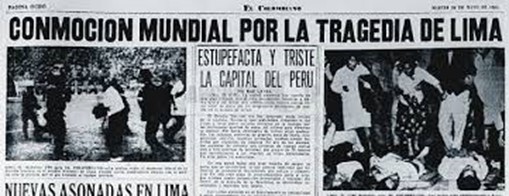

THE TRAGEDY OF THE ESTADIO NACIONAL OF LIMA

It is 24 May 1964. The qualifiers for the upcoming Tokyo Olympics are being played. The formula that will bring two South American national teams to fight for Olympic gold is rather peculiar.

The seven participating Under-23 teams are those of Argentina, Brazil, Peru, Chile, Colombia, Uruguay and Equador.

Each of them will face all the others in a single round that will all be played in Lima, the capital of Peru, in the ‘Estadio Nacional’, the country’s most important and capacious stadium.

It starts on 7 May with Peru vs Uruguay and will close on the 31st of the same month with Peru vs Brazil.

On that day, the hosts face Argentina.

The Albiceleste has an immaculate roster up to that point. Five matches and five triumphs. It means a foot and a half on the plane that will take them to Japan to contest the Games in October of that same year.

For Peru, however, the match has a very different value. Chumpitaz and his teammates are in second place, tied with Brazil, and scoring points against the Argentinians is crucial for them.

Inside the stadium there are almost 50,000 spectators, practically all Peruvians, ready to support their boys.

The first half saw Peru constantly forwards in search of a goal, but the Argentine defence, centred on the already charismatic captain Roberto Perfumo (who would also captain the Argentinians ten years later at the 1974 World Cup in Germany), held out without too much trouble.

It was the Argentinians, however, who found the way to the goal after a quarter of an hour or so in the second half.

It was Rosario Central midfielder Néstor Manfredi who put his side ahead with a fine shot on the turn after a short clearance by the Peruvian defence.

Peru’s reaction was vehement.

A draw would keep their hopes of qualification alive.

And the equaliser came.

Seven minutes to go when, on a cross from the right by Enrique Rodriguez, centre forward Enrique Casaretto headed the ball towards the second post.

Argentine right-back Andrés Bertoletti seemed to be ahead of the ball and tried to volley it back. On that ball, however, Peruvian left winger Victor Lobaton pounced and stretched out his leg in an attempt to anticipate his marker.

He failed to do so, but the deflection of the young Argentine full-back from Chacarita Juniors hit the shin of the Peruvian number eleven.

The ball changes trajectory and ends up in the back of the net defended by Augustin Cejas.

It is the goal that makes the stadium explode. Peru is alive and the Japanese Olympics are a little closer.

But at that point something happens.

Something that will turn a football match into an absurd tragedy of unimaginable proportions.

The referee, the Uruguayan Angel Pazos, is already running towards the centre of the pitch.

He is first chased and then confronted head-on by Perfumo.

He signals unequivocally that Lobaton’s leg was too tight and too high.

A ‘falta de plancha’ they call it over there. ‘Tense leg, dangerous play’ are the terms we use here.

And at this point happens what very but very rarely happens on a football field.

The referee changes his mind.

He awards a free kick to the Argentinians and cancels the goal.

The Estadio Nacional explodes with rage.

The protests are furious, uncontrolled.

Players, staff and public.

The incident is indeed peculiar and highly unusual and the frustration of the Peruvian fans is evident.

In those agitated moments, two fans, Victor Melasio Campos (known as ‘El Negro Bomba’ because of his ‘important’ size), a notorious troublemaker with several criminal records, and Edilberto Cuenca cross the barriers and enter the playing area.

There are only two of them.

El Negro Bomba is immediately knocked down and rendered harmless by a swarm of policemen while Cuenca is given even harsher treatment. Peruvian police dogs are also set on him. And here begins a series of situations that as usual change depending on who is telling them.

What is certain is that Cuenca, the second invader, faints. Someone (the referee of the match and the Chief of Police Jorge de Azambuja) claims that ‘fright’ is the cause of his fainting. For many other witnesses this is not the case. He was beaten savagely by the policemen. What is certain is that the scene was seen by all 47,000 fans in the stands, who at this point start railing even more against the police, threatening a gigantic pitch invasion.

The police lose control. They start throwing tear gas into the stands.

Within seconds panic breaks out, the ‘beast’ that is most difficult for human beings to control.

Everyone looks for an escape route, the crush becomes of gigantic proportions.

A tide of people rushes towards the exit gates to escape the gas and the crush.

But the iron gates of the stadium are all strictly closed.

This choice had been made to prevent the thousands of ticketless fans around the stadium from forcing their way through the police cordon trying to get in to watch the match as well.

A choice that would prove disastrous.

In the meantime, the referee, terrified by what was happening, had already rushed to the locker room, whistling the end of the match prematurely.

Yet another bad choice.

Tempers become even hotter.

The players lock themselves in the locker room, which is right under the grandstand where dozens and dozens of tear gas grenades have been thrown.

They hear everything and what little they see through the small window of their dressing room is something apocalyptic.

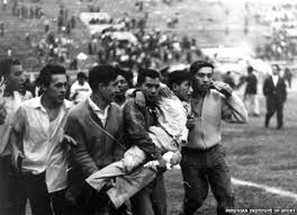

When they come out of the changing rooms several hours later, the scene before their eyes is unreal.

Dozens of bodies on the bleachers, near the exits and people running desperately for their sons, brothers and husbands.

When ‘the counting’ begins, the scale of the tragedy immediately appears for what it is: a massacre.

There will be 328 dead, not including those outside the stadium in a night that will be one of genuine terror for Peru.

There will be those who will seek revenge against the police (four officers will be killed in clashes in the streets of Lima) and there will be those who will take it out on vehicles, shops and factories.

The Peruvian government, beyond condolences and seven days of national mourning, will not know how to go about it. Only two will be the ‘culprits’ of that authentic massacre.

“El Negro Bomba” and, after a trial set up seven years after that May day, Police Chief Jorge de Azambuja will be sentenced to thirty months in prison.

This was ‘the idea of justice’ for three hundred and twenty-eight families who had lost a loved one.

And football? For what it can count after such a day, the decision will be taken to stop the qualifying round. No more matches will be played at the Estadio Nacional or in any Peruvian stadium.

The classification is ‘frozen’.

In second place tied were Brazil and Peru. It will be them, in a single match to be played in Brazil, who will compete for the second good ticket to the Olympics. There will be no match. Two weeks after that tragic day, Brazil, in its Maracanà, defeated the Peruvian national team by four goals to zero.

It is still today the greatest tragedy linked to a football event.

And as they say in Peru even today ‘as painful as it is to remember that day … it is a duty to do so’.