MILUTIN IVKOVIC: Pride and death of a special man

“I couldn’t say no.

Not to my old comrades from many battles where with our small team we tried, often succeeding, to hold our own against big teams like Gradanski Zagreb, Hajduk Split or my old comrades from FK Jugoslavija.

I couldn’t say no to my friend Milovan Jakšić, ‘the great Milovan’, the only one of my teammates in BASK who was with me on the ship that took us to Uruguay in 1930 to play the first World Cup in history.

I couldn’t say no to our fans who came by all means to watch our games, including those who would even travel 70 or 80 kilometres by bicycle to follow us when we played far from Belgrade.

I couldn’t say no.

Even though I haven’t played football for several years now.

I’ve already turned thirty-seven and now there are other priorities in my life that are far more important than running after a ball … even though I really enjoyed it and I didn’t do it badly at all.

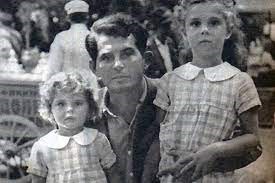

I have two wonderful daughters, Gordana and Mirjana, who no longer have a mother.

My beloved Ella was taken away by tuberculosis almost five years ago now and my time for them is the most important in my life.

The rest I dedicate to my patients.

I am a doctor.

I never stopped studying even when I played football for FK Jugoslavija and my country’s national team.

For the past couple of years, however, more problems have arrived.

In the form of cruel and ruthless invaders from a country that doesn’t even border on us but is led by a criminal madman with uncontrolled delusions of grandeur.

And I cannot stand by and watch.

I love my country, which has always given me everything I needed.

Now the time has come to reciprocate.

Many of us are doing so, even though we know that they are ruthless and that they can count on the help of wicked traitors to our country, first and foremost that puppet they have placed as head of our government.

But I am happy to play this game!

At least for ninety minutes I won’t have to think of anything else but trying to do what I’ve been doing for years: stop my opponents, keep them as far away from our goal as possible, and … maybe throw it into the back of the net from the other side with one of my headers.

It is 24 May 1943.

Just over two weeks have passed since that match, which was nothing more than a commemorative game to celebrate 40 years of BASK, the team where ‘Milutinac’, as he was called by everyone, had ended his career almost eight years earlier.

His name was known to the local authorities, who were subservient to Hitler’s Nazis.

He had already been arrested, beaten and held in prison several times.

This time, however, when there is a knock on his door in the middle of the night, there are many who pick him up.

“He is one of the communist subversive leaders, someone working undercover for the partisans”.

This is the ‘tip-off’ of some of his compatriots.

There will be no trial or prison sentence.

The following morning, Milutin Ivković will be shot by his compatriots in the name of the cowardice of one who kills a brother to comply with the wishes of foreign invaders.

The body will never be found, but as an old Navajo proverb says, ‘I do not need a grave to be remembered. If I have lived worthily I can be found anywhere’.

ANECDOTES AND TRIVIA

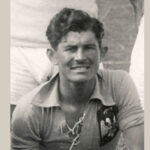

Milutin Ivković entered the youth sector of SK Jugoslavija, the team that would become Crvena Zvezda or Red Star in 1945. His talent is accompanied by a powerful physique and great determination.

He is a born leader and due to his physical prowess is deployed in defence, a role in which he will play his entire career. He quickly became the leader of the team with which he would win two titles, in 1924 and 1925. It was in October 1925 that he made his debut with the Yugoslav national team with whom he played thirty-nine matches, the last of which against France in December 1934.

In 1930, at the age of twenty-four, he would board the ship that would take Yugoslavia to the first World Championship, the one to be held in Uruguay.

Not only would the Yugoslavs be the only European team among the four that set sail from Europe (the others being Belgium, France and Romania) to get through the first round, but after beating Brazil, one of the favourites for the tournament, two to one, they would face the hosts Uruguay in the semi-finals.

It will be a real robbery.

Having taken the lead with a goal by Vujadinovic, the ‘plavi’ were caught up and overtaken before having a goal disallowed for an extremely dubious offside.

The real scandal happened a few minutes later when the Uruguayan striker Peregrino Anselmo deposited in the net the goal of three to one … after having received a pass from a policeman who had kicked a ball that was coming out of the rectangle towards him!

It seems that on that occasion Ivković, Yugoslavia’s captain, approached the match director, the Brazilian Almeida Rego, asking for an explanation for such a blatantly irregular action.

“I had to do it this way son. It’s the only way we can get off this pitch alive’.

Legend has it that even a character as proud and rebellious as ‘Milutinac’ avoided controversy for once …

The scandalous refereeing was obviously not well digested by the Slavs, who decided on the spot to return home, refusing to play the ‘final’ for third and fourth place against the United States. In the ‘all-star’ line-up of the tournament, the one with the best eleven players in the event, there were nine South Americans (seven Uruguayans and two Argentinians) and only two players from other nations: the US striker Bert Patenaude and … Milutin Ivković!

It seems that during that World Cup ‘Milutinac’ received offers from various clubs in Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina to convince him to stay and play professionally in those countries. This time it was not only love for his native country that convinced him to return to Serbia.

Waiting for him was his love, Ella, whom he married a few weeks after returning from the World Cup.

In 1934, the robust Serbian defender (he was 188 centimetres tall) graduated in medicine. He opened a practice in Belgrade shortly afterwards, specialising in dermatology.

It was at this time that his political involvement became important. The growing danger of Nazi Germany will push him to become one of the promoters in his country of the boycott campaign at the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

In 1938, in the year of his wife’s death, he became the editor of the ‘Young Communists’ newspaper called ‘Miadost’ (Truth).

When Germany, supported by Mussolini’s Italy, invaded Yugoslavia in June 1941,

Milutin Ivković soon realised that there were not only the invading enemies to fight but also the terrible ‘Ustasha’, a clerical-fascist group that immediately became allies of the Germans and Italians.

They were to be the torturers of ‘Milutinac’ in their ‘crosshairs’ from the start of hostilities.

On the morning of 25 May, when he is taken to the Banjica concentration camp, Ivković soon realises that his fate is sealed.

It is said that for a moment he managed to wriggle out of his torturers’ grasp and get close enough to the camp commandant Svetozar Vujković to spit in his face.

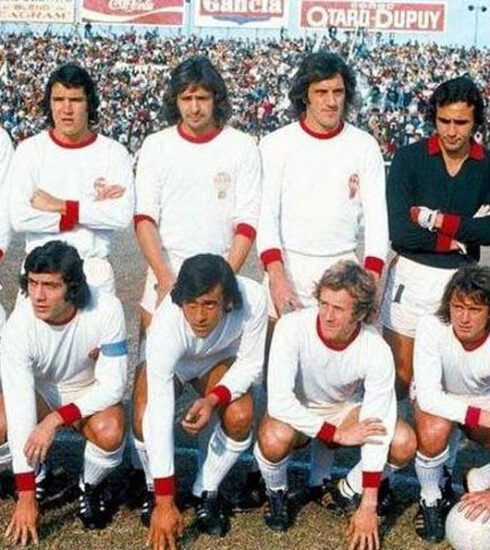

Milutin Ivković is one of the very few in the history of Serbian football to be equally remembered by Belgrade’s two great football rivals.

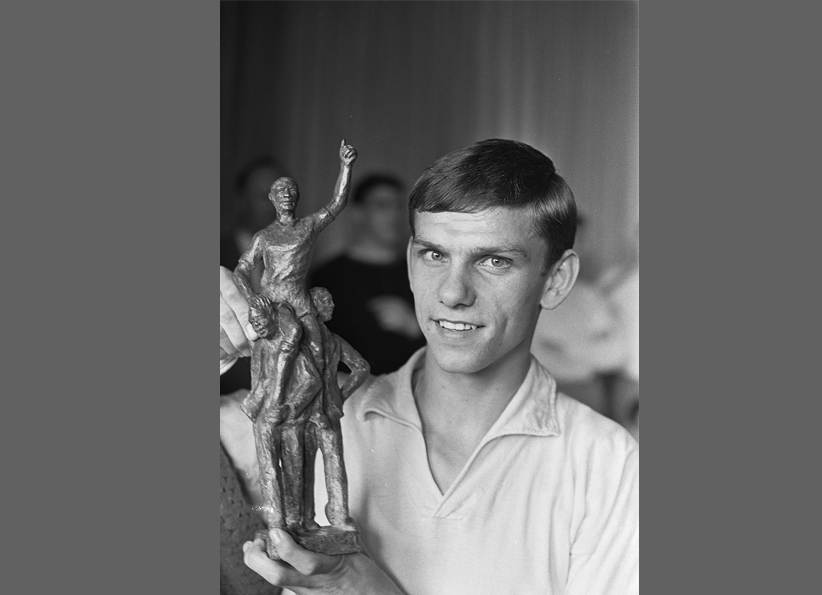

As early as 1951, the authorities erected a statue in his memory in the JNA stadium, which is now FK Partizan’s stadium, and an adjacent street named after him, Rajko Mitić (the famous ‘Marakàna’).

Finally, a statue in his honour was erected just outside the same stadium in 2013.