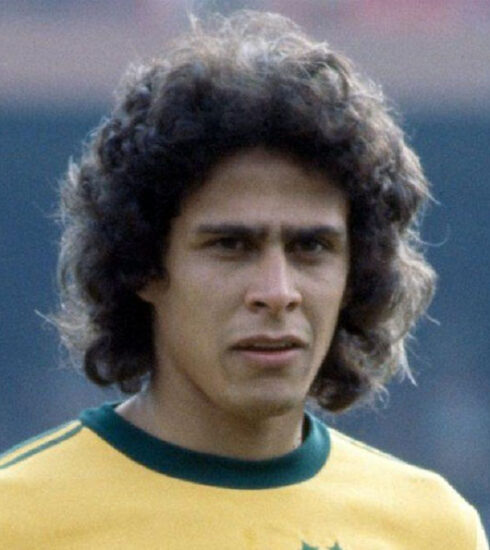

JOE JORDAN: more Scottish than the kilt

When he arrived at Leeds in the summer of 1970 no one had ever heard of him. Don Revie, the great Middlesbrough manager who had taken Leeds United back to the top of English football, had wanted him.

Joseph Jordan had played a handful of games for Greenock Morton, a team in the Scottish cadet league. And for someone who played in the centre of the attack, you cannot say he had done wonders. Just one goal in eight official games.

Only that Revie had been following the boy since his early days in the youth ranks at Blantyre Victoria thanks to the advice of a friend who lived in the area.

“We have a diamond in the rough here Donald. But hurry up and come see him because apparently Jock Stein and Bill Shankly have also started asking about him,’ the friend told him over the phone.

What better reference than the two greatest Scottish coaches of the era? And if two big teams like Celtic and Liverpool were interested, it was really worth a shot. That was more or less what Don thought in that spring of 1970.

The Leeds manager took his car, crossed the Pennine Mountains and drove through Hadrian’s Wall. Almost 400 kilometres to go and see a carnivore like Joseph Jordan in action.

Forty-five minutes of game time was all it took for Revie to decide that the 186 centimetres, 80 kilograms of muscle big lad could do the trick for his Leeds side.

“I don’t know if he will become the footballer I think he will be, that only time will tell. All I know is that you will come to me and beg me to put him in the team with you in training matches.”

Those were Revie’s words when he told his players that he had acquired this unknown Scottish semi-pro.

It only took Jack Charlton, Norman Hunter, Johnny Giles and co. a few training sessions to realise that their manager had not exaggerated at all.

Not only was he a genuine scorer but his style of play made every ball a matter of life and death.

No compromise.

And in the aerial game he was unrivalled.

Power and elevation.

And a musculature in his neck that allowed him to impart impressive power to his headers.

‘I had never in my whole career lost three aerial duels in a row,’ Jack Charlton, Leeds central defender and world champion with the English national team in 1966, recounted one day.

“Against Jordan in training I got to five …”

The problem for the Scot was that there were two strikers in the first team of the calibre of Mick Jones and Allan Clarke who not only scored with impressive regularity but had built up an almost telepathic understanding.

Jordan knew how to embrace his moment.

In the first few seasons he played very little but those who saw him in action with the reserve team knew it was only a matter of time.

The breakthrough season was 1972-1973. It was during this period that the problems of Mick Jones, up to that moment the unquestionable holder of the Whites’ number 9 jersey, finally gave Jordan the chance to play with continuity in the starting line-up.

Jordan responded magnificently, scoring twelve goals in thirty-four official games but above all fully confirming his skills as a ‘target man’ of the highest level.

It would be a season that would end in the most bitter way possible for Jordan.

First the exclusion in favour of Jones in the FA CUP final lost against Sunderland and then the incredible and undeserved defeat in the Cup Winners’ Cup final in Thessaloniki against AC Milan, where ‘Big Joe’ played as a starter but failed to make his mark.

Three days after that match came his debut with the Scottish national team in an Inter-British Tournament match against ‘the Auld Enemy’, England.

It was another defeat and again by one goal to nil like the previous two.

A few months would pass and one of the greatest satisfactions of his entire career would come for Joe Jordan.

Scotland received Czechoslovakia at Hampden Park in a World Cup qualifying match in Germany the following summer.

A win would guarantee a place in the final sixteen … sixteen years after the Scots’ last appearance in a World Cup final, in Sweden in 1958.

The start is disastrous. A seemingly innocuous shot by Zdenék Nehoda escapes the grasp of Scotland goalkeeper Ally Hunter and rolls into the net.

Scotland reacted vigorously and before the end of the half found the equaliser with a header from Manchester United central defender Jim Holton.

In the second half, however, Scotland’s attacks clashed relentlessly against the wall erected by Pivarnik and his team-mates and neither Kenny Dalglish nor Denis Law could find a way through.

Midway through the second half Scotland manager Willie Ormond decided to throw Jordan into the fray.

With Czechoslovakia becoming more and more curled up in their own area and space increasingly limited, other solutions had to be sought.

Joe Jordan’s header could be one of them.

Not even ten minutes had passed since the mighty Leeds striker had entered the field when Willie Morgan, the lanky Manchester United winger, from the right-hand side with a delicate outside-right touch, put a ball towards the centre of the Czech penalty area.

On that ball Jordan dives and hits the ball with a full forehead.

The ball went close to the post to the left of Czech goalkeeper Viktor, who was immobile on Jordan’s imperious shot.

It is the qualifying goal and it is the goal that will consign Joe Jordan forever to Scottish football history.

Joe Jordan would remain at Leeds United until January 1978 when Manchester United paid the astronomical sum of £350,000 to bring him to Old Trafford.

ANECDOTES AND TRIVIA

Jordan’s famous toothless look comes from what happened in one of the very first matches he played as soon as he arrived at Leeds. In a Championship reserves match during a scrum in the box, Jordan decided to dive head first to hit the ball just as a defender was trying to return it … but with his foot! The result was the loss of his two upper incisors … making him even more aggressive and intimidating.

Upon arriving at Leeds Jordan quickly fitted in with the large Scottish colony that played in the Elland Road team. Bremner, Harvey, McQueen, Gray, Lorimer were all important members of the team and Jordan soon became one of the company’s leading ‘jokers’.

During one of the classic harsh Yorkshire winters at training, Jack Charlton, the 1966 World Champion England defender, turns up in a brand new car.

Billy Bremner, Allan Clarke and Jordan himself manage to get hold of Charlton’s car keys and build a perfect snowman … placing him inside the car on the passenger seat.

“Charlton literally went out of God’s grace. He searched desperately for the culprits for days but no one said a word. I can tell the story now but at the time I was very careful!” says Jordan today with amusement.

“A sense of humour has never been Jack’s greatest asset,’ Jordan recalls.

Joe Jordan was to be one of the protagonists in what will be remembered in the history of the competition as the greatest theft in a Champions Cup final.

It is 28 May 1975. Leeds, who no longer had Don Revie on the bench who had meanwhile become the coach of the English national team, led by Jimmy Armfield played an excellent game, repeatedly putting Bayern Munich, the defending champions, on the ropes.

In the first forty-five minutes of the game there were two sacrosanct penalties for the English team that were not whistled by the French referee Kitabdijan, one in particular for a very clear foul by Franz Beckenbauer on Allan Clarke who had jumped him cleanly in the area.

Jordan dominated on high balls and it was an absolute monologue for Leeds, who reaped the benefits of their superiority around the quarter-hour mark of the second half. There was a free-kick from the three-quarter by Johnny Giles, Paul Madeley’s header into the centre of the area. The Bavarian defenders’ rebound was short and Peter ‘thunderbolt’ Lorimer volleyed the ball past an immobile and stunned Sepp Majer.

It was the goal of the English lead.

As the Leeds players are intent on celebrating their deserved lead, the referee can be seen pointing to a spot inside the penalty area on the signal of one of his linesmen.

The Bayern players are at least as stunned as the Leeds players.

The goal was disallowed for an offside call by Billy Bremner that was not only non-existent but completely irrelevant to the action as he was not in the path of the shot.

Within ten minutes came the two German goals by Franz Roth and Gerd Muller to seal one of the most sensational ‘thefts’ in the history of European football.

Only a few days have passed since that final. The Leeds team is in the classic end-of-season retreat in Spain.

The maitre d’ of the hotel walks up to the Leeds players and announces to them that the coach of Bayern Munich is on the phone and asks to speak to Joe Jordan.

Jordan casts a quick glance around at his teammates in the area and when he realises that both John Giles and Billy Bremner, the two jokers in the company, are missing, he is convinced that this is yet another prank of theirs.

“Gordon,” says Jordan to team-mate McQueen, “would you mind going and hearing what the Bayern coach wants?” increasingly convinced that this is yet another prank by his team-mates.

McQueen, posing as Jordan, discovers that Dettmar Kramer, the coach of the Bavarians, is on the phone telling him that Bayern Munich is interested in buying the Scottish centre forward.

McQueen seizes the opportunity.

“OK Mister Kramer. I will gladly sign for Bayern Munich … but only if you buy my friend Gordon McQueen in addition to me.

At this point, the Bayern coach explained that this was not possible as Franz Beckenbauer and Hans-Georg Schwarzenbeck were in the centre of Bayern’s defence and that there would be no room for McQueen.

At that point, a disappointed McQueen returned to the edge of the pool and told Jordan, ‘Boh, I didn’t understand who it was, but he did have a thick German accent!

The thing seems to end there.

On the last day of the holiday the scene repeats itself.

Kramer calls back and this time Jordan rushes to answer.

“So Mr Jordan, have you thought about our offer?” the German coach asks him.

When he is about to answer “Sorry, what offer Mr Kramer ?” suddenly it all becomes clear to him.

“Gordon McQueen is one of the best friends I have ever had … but I swear I would have gladly throttled him with my own hands that day!” says an amused “Big Joe” today.

On his return to England, Bayern made a formal bid for Jordan but Leeds were adamant they would not budge … and so Joe Jordan’s experience abroad was postponed for several years.

For any Scottish footballer, the match of the year was against the English ‘enemy’ in the defunct (and beautiful!) Inter-British Tournament.

Having lost on its debut in 1973, the following season, in May 1974, England and Scotland faced each other this time at Hampeden Park in Glasgow. There were almost 95,000 people in the stands. On that occasion Scotland triumphed by two goals to nil and Joe Jordan scored the first goal.

“After the game we drove from Glasgow back to Leeds. There was me, Harvey, Bremner and Lorimer … all Scots! while the fifth was Norman Hunter, the only Englishman in the group. For him that trip was pure hell. Billy Bremner, sitting in the back with Hunter, looked him straight in the eye the whole way with a sunny smile on his face’.

Joe Jordan was also on the pitch on the day of the unforgettable triumph at Wembley on 4 June 1977. “I don’t know how many Scots were there that day at Wembley … I do know that everyone I met in the following weeks told me they were there that day … so there must have been at least half a million!” says Jordan with amusement.

“All I know is that they were everywhere after the game, even under the showers in the changing rooms,” recalls the Scottish centre forward of that memorable day.

But not everything went right that day.

“At the end of the game I get into the car with my wife to drive back to Leeds. We drive a few kilometres and the car breaks down. Luckily we met three English fans who were infinitely kind enough to drive us to a train station,” recalls Jordan, who then adds, “They were the only three English fans I met that day!” He then bursts into laughter.

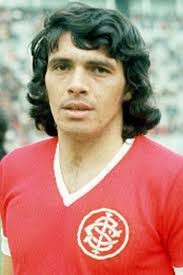

After his experience at Manchester United came the longed-for call from the continent for Jordan. It was AC Milan who brought him into their ranks in 1981.

Even though he is only 30 years old, the many seasons ‘waging war’ in opposing areas are beginning to take their toll.

Jordan has probably already begun his downward parabola, but to tell the truth, the Milan of that period is certainly not able to put him in a position to perform at his best.

It was a fragile Milan side that often had to defend against far superior teams and Jordan ended up playing many games as the only striker, often isolated from the rest of the team and without those supplies from the flanks that had made him one of the most feared strikers in Europe.

In fact, the start in the Coppa Italia deluded the devil’s fans.

A brace against Pescara and then a fantastic header in the derby against Inter are a good calling card, but in the championship unfortunately things will go very differently.

Only two goals in 22 games and for Milan at the end of the season there is a return to the purgatory of the Serie Cadetta. Jordan, despite several offers from Great Britain, does not even think about leaving the Rossoneri.

Milan dominated the Serie B championship and Jordan, who was often paired in attack with the young Aldo Serena in a team finally set up with ‘front traction’ by new coach Ilario Castagner, scored ten goals in the league, nine of which came from a header, his speciality.

The following season, to the surprise of team-mates and fans alike, the club decided to do without the Scottish centre forward. For him there was an offer from Osvaldo Bagnoli’s Verona, which was establishing itself in those years as one of the most beautiful realities of Italian football.

Jordan, however, never managed to express himself at his peak performance levels and his importance in the team quickly diminished. At the end of the season it was back to England in the ranks of Southampton.

Joe Jordan will always remember the three seasons in Italy as the most important of his career and with some regret for having arrived in Italy when his best days were probably already behind him.

Also related to his Italian period, however, is an amusing anecdote.

For every player who played for the Scottish national team there is a gift from the federation of a souvenir cap, which in England was handed out for every appearance on the national team while in Scotland (typical of the thrifty characteristics of the Scottish people) the gift was one cap for every SEASON of national team service.

Jordan, who made his national team debut in 1973, played at least one consecutive game a year with his national team until 1982, when he played in the World Cup in Spain.

The last cap, however, while Jordan was here in Italy, never reached him.

At this point he called the Federation several times asking what had happened to his tenth cap, the one from the year 1982.

“We regularly sent it,” the Federation confirmed to him, adding that “at this point it will probably have been lost”.

Jordan’s disappointment is considerable.

“Excuse me but when did you send it ?” asks a displeased Jordan.

“We still have the note. “Shipped in September 1982 at the headquarters of INTERNATIONAL FC.”

… Jordan had to go to the headquarters of city rivals Inter where, fortunately, they had kept his precious cap …

Joe Jordan belongs to that short list of footballers capable of scoring at least one goal in three different World Cups.

With the Scottish national team Jordan managed it both in 1974 (against Zaire and Yugoslavia) and 1978 (against Peru) and also in the 1982 Spanish World Cup against the USSR.

When his career as a footballer was over Jordan began his coaching career.

After a brilliant second place in the league achieved on the Hearts bench Jordan mainly worked as head coach with, among others, Liam Brady at Celtic (Jordan’s favourite team) and Harry Redknapp at Totthenam.

Even on the bench ‘The Shark’, as he was nicknamed by the Rossoneri fans, lost none of his proverbial grit.

Very famous in this regard was his ‘face-off’ with Rino Gattuso during a Champions League match between the Rossoneri and Totthenam in February 2011 where the 60-year-old Jordan did not give an inch to the gritty and much younger Milan player.

“I would say Gattuso picked the wrong man to fight with tonight,” was the comment at the time from Spurs manager Harry Redknapp.