ANATOLI KOZHEMYAKIN: death of a talent

«Unfortunately, it is known. When bad luck gets in the way, there’s nothing you can do.

I was a jerk until recently, taking my job as a football player not very seriously. Beer and vodka, nights in clubs always looking for some rock band to listen to and maybe with the company of a pretty girl.

I thought it wasn’t so important to train hard, stick to schedules and discipline, and lead that very boring athlete’s life that practically all my teammates do.

I was so good that I thought my talent would be enough.

Then again, when at the Under-19 European Championships played in Czechoslovakia three years ago you prove as I did that you are one of the best 18-year-olds around it’s easy to think that it will all be downhill.

At the end of the tournament they awarded a young Englishman named Trevor Francis as the best player of the tournament … and there was half a riot as most of the Czech fans were convinced that I should be the one who deserved that award.

Someone started calling me the new “Streltsov” i.e., the best striker ever seen in these parts.

Well, he liked “living” a lot too !

I only hope to have a little more luck than him since he spent the best years of his career in a gulag …

When I came home with my Dynamo I was scoring a lot of goals and playing great.

I arrived in the national team the following year, in 1972, and that friendly with Bulgaria seemed only the beginning of an endless series of games together with the best players in my country.

There were already Onyscenko, Khurtsilava, Kon’kov, and youngsters about my age like Blokhin and Buryak were coming on the scene.

Then something changed.

Training became heavier and heavier, and going out at night more and more fun.

My performance dropped in level.

As was to be expected.

So many people told me.

My teammates, managers, and lifelong friends.

“Marry your girlfriend and you will see that the responsibilities will help put you at ease.”

They were right.

I got married and last year, 1973, I finally got back to playing at my level, at the level I had accustomed Dynamo fans and especially myself to.

We were three games away from the end of the championship. We were third in the standings and I was leading the scoring charts.

We were playing against Dnepr and I had already scored two goals.

With only a few minutes to go an opportunity presented itself for me to score the third.

On the ball me and Sergey Sobetsky, the goalkeeper of the Ukrainian team, arrived together.

Only I put my leg on it.

He his whole body.

Ruptured cruciate ligament.

The worst that can happen to a footballer.

“Right now dammit !”

I told myself every day.

Now that everything finally seemed to be going right.

Now that I was back in the national team, that I had started scoring lots of goals again.

The doctors said I would never play again.

Some even said I would be lame for the rest of my life.

Instead, less than 10 months later I was still on the field.

That was in August of this year.

I was welcomed as a hero, as a war veteran who had been given up for dead.

No one believed that I could come back and especially so quickly.

I played one of the best games of my life.

I seemed to have stopped playing the week before, not in October of the year before.

I was happy.

“Time is on my side” sang my beloved Rolling Stones.

And I am absolutely convinced of that now.»

After that wonderful game against Zaria Voroshilovgrad on his return from long injury for Anatoli Kozhemyakin come a series of less happy games.

His knee still gives him some trouble, and at that point Dynamo coach Gabriel Kachalin decides not to call him up for the next day’s game against Torpedo.

“Anatoli, take the weekend to recover. See you at practice on Monday,” are the words of his coach.

A Saturday night off after a long time.

“Mashina Vremeni” (Time Machine), the country’s most popular rock band and Anatoli’s beloved, is playing in Moscow.

He joins a couple of friends and decides to go to the concert.

When he returns home in the early hours of the morning, his wife is in a rage.

This is not the behavior she expects from a husband and the father of a daughter only a few months old.

She refuses to let him in.

Anatoli at this point is forced to ask a friend for hospitality.

There will be time the next day to apologize to his wife.

After all, by now he has gotten his head on straight and his wife knows it.

An evening a little out of the norm is no tragedy.

It is Sunday morning. Anatoli and his friend are ready to go out.

The Dynamo striker is going home, perhaps stopping by a florist to “sweeten” his wife.

The two take the elevator.

Between the third and fourth floors, however, the elevator suddenly gets stuck.

Anatoli and his friend hit the emergency button and then everyone else to no avail.

They wait a few minutes but then decide to act.

They open the elevator door and notice that the floor of the third floor is just below them.

The friend gets out and then invites Kozhemyakin to do the same.

“I don’t then feel like soiling my jeans!” replies Anatoli, who has always been jealous of his favorite “Western” garment.

They will be the last words of his life.

As he prepares to lower himself to the floor below, the elevator starts up again.

The friend will recount that he heard nothing, neither a cry nor a moan.

Anatoli Kozhemyakin, the greatest hope of Soviet soccer will die this way, crushed by an elevator.

He was only 21 years old.

There were many who said he was better than Oleg Blokhin.

ANECDOTES AND TRIVIA

After avalanches of goals scored in the youth ranks of Lokomotiv Moscow for “Tolya” (that was his nickname) came the call from Dynamo Moscow, the team where Lev Yascine is playing the last remnants of a glorious career.

At his first training session, the very young Anatoli shows up in his “Teddy Boy” style. Hair a little longer than the norm and most importantly in his beloved blue jeans.

Lev Yascine look at him from head to toe for several seconds and then, turning to his teammates in the locker room asks, “Did any of you happen to call a plumber?”

Also Yascine somehow stars in the debut of “Tolya” in the colors of the team of the Ministry of the Interior and dear to the KGB.

After entering in the last few minutes of the game against Torpedo on May 2, 1970 four days later Anatoli is deployed from the start against Chernomorets.

Kozhemyakin enchants everyone. Comrades, opponents and observers. He doesn’t score (although he comes very close by hitting a crossbar) but his technique, elegance, and dribbling immediately leap out at the onlookers.

He is more than six feet tall, lean and extremely coordinated.

At the end of the game, reporters approach Lev Yascine.

“Lev, but who is that kid who was playing up-front today? He looks really good!”

The Soviet goalkeeper’s reply is already a sentence.

“He is so talented but talent without hard work leads to nothing.”

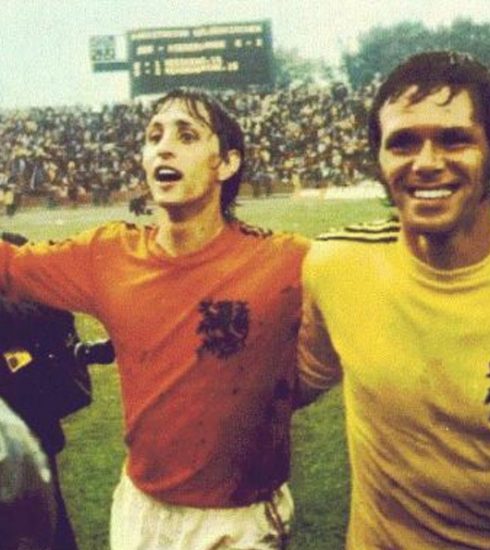

In the Soviet Under-18 Nation entering the European Championships in Czechoslovakia are two formidable talents.

Oleg Blokhin and Anatoli Kozhemyakin.

“The forward line of our national team is fine for the next ten years” is the consideration of Soviet journalists and soccer fans.

In those European Championships, however, “Tolya” literally eclipsed his teammate, who only four years later would win the Ballon d’Or.

Kozhemyakin will be the tournament’s top scorer with seven goals in five games and will finish second (not without controversy) in the ranking of the tournament’s best soccer player behind England’s Trevor Francis, who will win that edition with his England team.

There will be one goal in particular that will remain in the memory of those who were present at that tournament.

In the match against Belgium “Tolya” receives a long ball from the back.

He stoops it with his chest, slips it onto his thigh, lifts it up and then fires a powerful shot from over twenty meters that goes into the Belgian number one’s goal.

All in half a meter of space and without the ball touching the ground.

Kozhemyakin’s love of rock music, nice clothes, champagne, foreign beers (Czechoslovakian in particular) and alternative nights soon put Kozhemyakin in the crosshairs of the Soviet leadership.

They do not want him to become another Streltsov or another Voronin, great players but who because of their “Bohemian” habits saw much of their talent wasted.

Every “crooked” game was attributed to his lifestyle, and his decline in performance in 1972 was accompanied by all kinds of rumors.

“Tolya” was probably no different from many boys his age in the West, but it is equally obvious that his “passions” were on a collision course with the ascetic and rigid world of the Soviet Union at the time.

Rock music was a major attraction. He especially loved Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones, and it is said that on every trip abroad Kolya would literally hoard vinyls of his favorite bands.

It definitely made headlines when one day he presented himself to his teammates in a Denim suit, which was more unique than rare in the USSR at the time, and equally renowned was his appreciation for champagne even though there are many, first his former teammates Anatolij Bajdačnyj and Aleksandr Machovikov, who categorically denied that “Tolya” was a heavy drinker.

At the end of his first season with Dynamo came a triumph in the USSR Cup that gave the Muscovites the right to play in the Cup Winners’ Cup in the 1971-1972 season.

It was to be a resounding path in which Kozhemyakin would often star, though not always in a positive way for his club.

In the quarterfinals for Dynamo is the strong Red Star of Belgrade.

“Tolya” will score both in the first leg match, won by two goals to one, and most importantly the equalizing goal at the Belgrade “Marakàna.”

In the semifinals, however, a very peculiar episode would happen that threatened to jeopardize the Moscow team’s run to the final.

During a scrum in Dynamo’s penalty area, a teammate of Kozhemyakin, Zhukov, fell to the ground struck by an opponent.

Certain that he heard the referee’s whistle, Kozhemyakin takes the ball in his hand to take the free kick in his favor and restart the action.

… only there was no referee whistle, which instead punishes Anatoli’s offense with a penalty kick.

Fortunately, the Soviets, after the two one-to-one draws, would prove infallible from the eleven meters winning the right to play the final in Barcelona, which they would later lose to Glasgow Rangers … with Kozhemyakin absent due to injury.

The first to learn of Anantoli Kozhemyakin’s death was Lev Yascine himself, who has since become a prominent Dynamo executive.

It is he who a few hours later goes to the field where Dynamo is to play its match with Torpedo.

He meets a journalist who simply asks him how he is doing.

“Bad,” replies the now former Dynamo goalkeeper, “I’m really sick today,” but without adding anything else.

The first to know will have to be Anatoli’s teammates.

They have just lost one-nil to Torpedo and when Yascine enters the locker room they are still arguing heatedly.

He shushes everyone.

“A defeat in soccer is just nonsense. Just now your comrade “Tolya,” Anatoli Kozhemyakin left us” before bursting into tears.