ANDREA FORTUNATO: The torn dream

“At the end of training, the coach took me aside.

Four words in all.

Those words that anyone who is a professional footballer dreams of hearing from the coach of their country’s national team.

‘Tomorrow you will play from the start’.

It was Arrigo Sacchi, coach of the Italian national football team, who said them.

I would have liked to hug and kiss him!

… only Arrigo Sacchi is not exactly the most expansive person on this earth… better not to risk him changing his mind!

So I confined myself to a toothy grin plastered on a probably dumbfounded face and accompanied by one of those run-on sentences, even a rather stupid and banal one.

“Thank you coach, I will do my best” was all I managed to say to him, drunk as I was with immense emotion.

Tomorrow, 22 September 1993, against Estonia here in Tallinn, I will be on the pitch with the number 3 in a qualifying match for next summer’s World Cup to be played in the USA … and to be among the 22 who will board that plane to the USA would be another dream come true.

To tell the truth, the signs that Sacchi held me in high regard were all there.

In the morning game when Carlo Ancelotti, Sacchi’s deputy, handed out the jerseys and handed me the white one, I squinted my eyes.

It was the exact same colour as Baresi’s, Costacurta’s and Benarrivo’s … the other three starters in the defensive department!

This didn’t guarantee me anything of course … but it could only say one thing; that Mister Sacchi believed in me and that perhaps my debut in the national team was much closer than I thought.

For the entire 45 minutes of the match, both Sacchi and Ancelotti corrected, advised, resumed and encouraged me.

I know very well that the number three jersey of the national team belongs to Paolo Maldini, perhaps the strongest left-back in the world. But I also know that if there is a need I will be ready.

Starting tomorrow.

Tomorrow night I will have a number three jersey to take home to my family.

My mother thought I was crazy when I left our beautiful house in Salerno to go up there to Como!

I was only thirteen but I knew, I felt, that football would be my life.

I promised my parents that I would continue studying anyway.

“I will,” I promised them, “but you can be sure that it won’t be this accountant’s diploma that will give me the job in life.

And when I see them again and hand them this jersey, perhaps they will have definitively understood that I was right.”

Just under eight months have passed since the best day of Andrea Fortunato’s career.

Only now it seems like a different story.

In fact, it seems like someone else’s story.

For several weeks now, Andrea Fortunato’s performance has sensationally dropped.

In the penultimate game of the season in the Piacenza away match, which ended in a dull 0-0 draw, he was substituted halfway through the second half after yet another colourless performance.

There is almost no trace left of that physical exuberance that allowed him to run up and down the left flank dozens of times a game, where you could find him closing down a defensive diagonal or stealing a ball from his direct opponent with a robust tackle, and the next thing you know he is pushing the ball at the foot of the opponent’s three-quarter and putting inviting crosses into the middle of the area for the heads of his friends Vialli and Ravanelli.

Instead, Andrea now limits himself to ‘homework’, holding his position, trying not to leave too much space for his direct opponent, hoping for that ‘6’ in the sporting newspapers’ report cards, which instead arrives more and more rarely … while instead the failures, often pitiless, are more and more frequent.

It’s a sudden and unexpected involution that triggers perplexity in the Juventus management, in the insiders and, above all, a lot of anger in the fans of the ‘old lady’ who, with the complicity of the team’s increasingly opaque performance, are looking for a scapegoat on which to vent their frustration, as always in these cases.

Andrea Fortunato is the perfect target.

The boy from a good family who has never really been ‘hungry’, who in just two short seasons has gone from Serie B to his debut in the national team … and who in all likelihood has sat on his laurels, indulging in the ‘good life’, nightclubs, easy girls, and maybe even a few forbidden vices.

The irrefutable fact is that Andrea Fortunato is struggling more and more.

His energy seems to run out at the speed of light, in training as well as in the game, and the feeling of feeling ‘drained’ is repeatedly expressed to staff, teammates and management.

Andrea is actually a very serious boy, with the great sense of ethics handed down to him in his family, and he does not give himself peace for that devastating drop in performance.

Then comes the 20th of May 1994.

The championship had been over for a few weeks and Juventus, deprived of its many national teams, was engaged in a friendly match in Tortona, to celebrate the promotion of the local Derthona team to the Eccellenza championship.

Andrea took the field from the start.

But he is the ghost of himself.

He constantly struggles against opponents who only a few months earlier would have barely tickled him.

Yeah. A few months earlier.

When, after a brilliant start to the championship, Giovanni Trapattoni, the Juventus coach who is usually full of compliments towards his players, especially in front of the media, called him ‘the new Cabrini’.

There wasn’t a single pundit who didn’t see Andrea Fortunato as Paolo Maldini’s natural reserve for the American World Cup that was to begin a few weeks later.

At the end of the first half of that friendly Andrea instead asked for a change.

‘I don’t have an ounce of strength left’ were the only words he managed to say in the embarrassment of such a negative test.

At that point, however, the Juventus doctors, and in particular Dr. Riccardo Agricola, decided they wanted to see clearly.

They had Andrea undergo a thorough series of tests.

The response was devastating.

Andrea Fortunato was diagnosed with a form of acute lymphoid leukaemia.

It would almost be a relief for Andrea, so offended and humiliated by months of tendentious and malicious speculation against him, to be able to say ‘see? other than a good life! I’m sick. That’s why I could no longer play at my level’.

This is probably what Andrea Fortunato would have wanted to say to all his most ruthless detractors.

Except that one can die of this form of leukaemia.

So there is no time and probably not even the will to get lost in these things.

Instead, there is a very tough battle to face.

Andrea attacks it exactly as he did when he was storming through opposing defences on his beloved left lane.

There are his family, his lifelong friends and his teammates, Ravanelli and Vialli above all, who help him, encourage him and wait for him on the pitch to pick up where they left off.

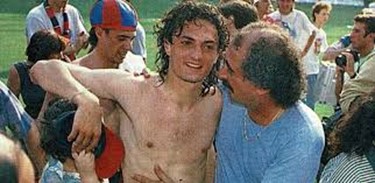

In October of that 1994, Andrea Fortunato left the hospital.

The cells received from his father Giuseppe had begun to take root.

Optimism sets in.

There is a whole life ahead and at this point even the football pitch is no longer a chimera.

A few training sessions with Perugia, the return home and then the great joy of returning to the group for Juventus’ away match in Genoa against Sampdoria.

It’s 26 February 1995

Andrea seems to have made it.

Instead it’s all ephemeral.

A banal pneumonia attacked that still fragile and defenceless body and took him away on 25 April 1995.

Andrea Fortunato, the new Antonio Cabrini, had yet to turn 24.

At the funeral, in his Salerno home, there were more than five thousand people to bid farewell to a young man who had left his city, family and friends more than 10 years before to pursue his dream.

And everyone’s hope is that Gianluca Vialli, his captain and great friend at Juve, was right, as he said goodbye to Andrea during the ceremony: ‘Let’s hope that there is a football team in heaven too… So that you can continue to be happy running after a ball.

Andrea Fortunato’s is one of the 38 stories told in