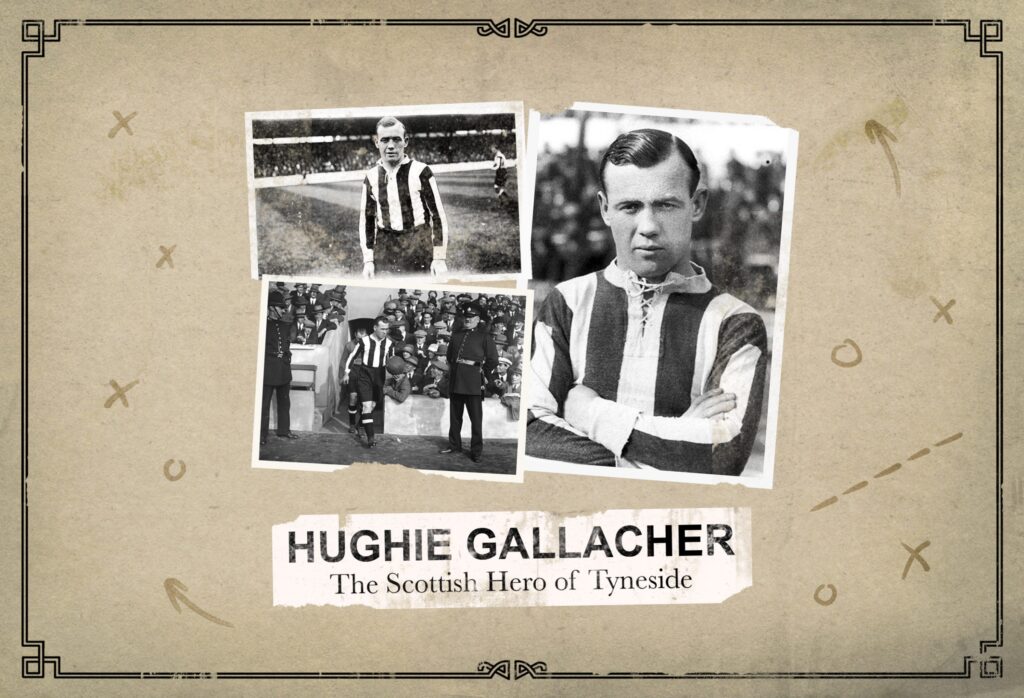

HUGHIE GALLAGHER: The tragic idol of Newcastle Football Club

In Newcastle upon Tyne they love football like nowhere else in England. There is no argument about that.

And it does not matter if the trophy cabinet is not full of titles, if the disappointments, sufferings and difficulties have, in the almost 130 years of the NEWCASTLE FOOTBALL CLUB’s existence, far outweighed the joys, triumphs and successes.

In Newcastle Upon Tyne people LOVE their colours, the black and white of a jersey, which for this ‘people’ of the North East of England, which has always been a working class area and is too often depressed and economically struggling, means much more than going to the stadium on a Saturday afternoon to support their team.

Being loved in Newcastle is something different for a footballer than being loved anywhere else in the UK.

You become a demigod.

And because WINNING has always been harder here than anywhere else, you end up falling in love with a symbol, a footballer who represents the club, the city and all the Geordie people.

Ask Alan Shearer what the love of the people of Newcastle is.

Ask Kevin Keegan or Malcolm Macdonald, or going further back in time ask Jackie Milburn.

All people who have passed through these parts, who chose Newcastle when there were different, perhaps more lucrative or successful possibilities.

A few fewer trophies and perhaps a less substantial bank account … but ask them all if they would have traded on the love they received here.

You will get the exact same answer.

Before all these champions there was another who pioneered this sort of devotion, of iconic and total recognition.

His name is Hughie Gallagher, a Scotsman just over 160 centimetres tall but who was the first true giant in the history of this inimitable club.

It is June 1957.

Hughie Gallagher has returned home from his usual evening visit to the pub.

He has always drunk his ‘Newcastle Brown Ale’ ever since he was the idol of the Newcastle Football Club many years before. For a few years now, however, things have got a bit out of hand.

Exactly since, seven years earlier, cancer took his beloved Hannah away.

Since then he has had to bring up three children on his own and sometimes the burden has been very difficult to bear. Like many before and after him, when his career was over, he realised that the world outside a football pitch is far more complex, crooked and dull than that green rectangle where, if you have talent, passion and a spirit of sacrifice, sooner or later the result always comes.

So many activities, so many attempts to fit in, to find a little place for someone who a quarter of a century earlier had made an entire people fall in love: the ‘Geordie’ of Newcastle upon Tyne, who when it comes to truly loving are second to none.

… ask Alan Shearer or Kevin Keegan or Malcolm Macdonald if you like …

He was even a journalist.

He had a sharp tongue when he played, with opponents and referees and his pen was no different. Sometimes even too much so. So much so that he was refused entry to ‘his’ St. James’ Park for some overly polemical and destructive comments towards the ‘Magpies’.

And now, at 54, all that’s left is three rented rooms in Gateshead, a handful of pounds in his bank account and three children of whom only the first has now become independent, becoming an RAF mechanic.

When he returns that evening from the pub only Matthew, the youngest of the three, is at home.

He is the most rebellious, the most headstrong … he is the one who most resembles his father.

They have an argument, one of many.

Hughie Gallagher loses control.

He used to do that on the field too sometimes.

Never been naughty but hot-blooded, like a proud, fighting Scotsman.

He throws an ashtray that hits his son Matthew in the forehead.

Blood comes out of the wound, lots of blood.

Matthew is a little stunned but apart from the wound there are no other consequences.

At that moment, however, Hughie Junior, the oldest son, comes in.

What he sees frightens and angers him. A violent argument ensues with his father, who apologises and tries to justify the incident.

A neighbour rushes in. He asks his older brother if he should call the police.

Hughie Junior agrees.

Even four policemen arrive and take the former football glory away as a murderer or rapist.

As they take him away Hughie Junior shouts everything at them, including a warning not to be seen in that house again.

The thing takes on huge proportions, exaggerated under the circumstances.

The tabloids wallow in it. It wasn’t much different then than now.

Hughie Gallagher is devastated.

Many people remember him walking slowly, automaton-like through the streets of Gateshead barely responding to the greetings of passers-by, him usually so jovial and smiling.

They saw him walk past, mutter an embarrassed ‘sorry’ and then throw himself under the train from London to Edinburgh.

One too many burdens to bear, yet another for the small shoulders of a man who had been as deeply loved in Newcastle as in his native Scotland.

Hughie Gallagher, born in Bellshill, a mining town south of Glasgow, actually went down the mine. Like everyone else in those parts.

The turning point came during a game of the Bellshill junior team. When they do the count they realise that a footballer is missing. They look among the few dozen spectators present and ask if there is anyone under 18 who can play football.

Hughie offers himself. He plays and scores the tying goal in the final one-on-one.

Less than a year later he makes his debut for the Junior National Team of Scotland.

Opponent is Ireland. It was again he who scored the equalising goal, with a splendid header just a handful of seconds from the end.

… from the height of his 164 centimetres …

The following year he played in the Scottish First Division, with Airdrieonians.

It would be four memorable seasons for the defunct Lanarkshire club, with three runners-up finishes in the league and the only trophy in the club’s history, the Scottish Cup won in 1924 in the final against Hibernian.

In 129 matches with Airdrie, Hughie Gallagher scored 100 goals.

By now he is such a big name in Scottish football that south of Hadrian’s Wall a furious bidding war has broken out between the English league bigwigs.

The threats of the ‘Diamonds’ fans, who turned up en masse in front of the club’s headquarters with several cans of petrol and declared themselves ready to set fire to the main stand at Broomfield Park, the club’s stadium, if the club decided to sell their favourite player, were to be of no use.

The winner was Newcastle prepared to shell out the impressive sum of £6,500 for the little Scottish centre forward.

It is December 1925

Gallagher is hailed as a hero and his debut in his new colours lives up to the hype. It’s a spectacular three-on-three against the great Dixie Dean’s Everton who will score all three goals for the Blues while Gallagher will have to ‘settle’ for a brace.

At the end of that first ‘half’ season he will score a beauty of 23 goals in 19 games.

But the masterpiece would come in the following season.

Hughie Gallagher would become Newcastle captain and this new important responsibility would raise his performance even higher.

At the end of the 1926-1927 season Newcastle, after overcoming strenuous resistance from Huddersfield and rivals Sunderland, would lift their fourth English league title … to date the last one won by the Magpies.

Gallagher would end his Newcastle career in the summer of 1930 when Chelsea decided to shell out a sum of money that could not be refused by the St. James’ Park club: at least £10,000 was paid out by manager David Calderhead for his card.

His career with Newcastle would end with an impressive tally: 143 goals in 174 appearances, with an average of over 82 per cent, something no other great number 9 in Newcastle’s history would ever manage to surpass.

Even after Chelsea, where he would continue to score with impressive regularity, he would never disappoint at any of the clubs in which he would later play. He would become an idol at Derby County and Notts County and after a brief spell at Grinsby would return to his beloved Tyneside, this time with little Gateshead, a town a stone’s throw from his Newcastle.

His presence alone would triple the attendance at tiny Redheugh Park, which regularly reached 20,000 during Hughie Gallagher’s time at the club.

He would retire in 1939 at the age of 36, remaining to live in Gateshead with his family.

ANECDOTES AND CURIOSITIES

One of Hughie’s passions as a boy besides football was boxing. It was common to see him train in a gym in Hamilton and cross gloves against guys much taller and more athletic than him.

“I was never afraid. Never. And the ring really helped me toughen up and realise that even on a playing field I could make anyone respect me.”

Gallagher marries very young. He was not yet 18 when he tied the knot with Annie McIlvaney, a peer he met while working in the mines. One of the couple’s sons, Jackie Gallagher, was an excellent striker for Celtic in the 1940s before a serious injury curtailed a promising career. The painful and painful divorce with Annie in 1923 cost Gallagher a fortune and he was even found by a court to be ‘insolvent’ while he was an accomplished First Division footballer with Chelsea.

As a footballer Hughie Gallagher was considered to be a true ace.

Despite his short stature (164 centimetres) and a lean physique he was virtually impossible to stop. He had a superlative technique, great speed and an uncommon football intelligence. One of his most classic plays was to drop back almost to the midfield line to receive the ball from his team-mates, turn and ‘aim’ at the much stronger (and slower) opponents’ defenders before unloading his deadly conclusions or putting his team-mates in goal with precious assists after having drawn the attention of the opponent’s defence.

His elevation was also proverbial, allowing him to score an impressive number of headers.

Despite the fact that he loved (without ever having an overt drinking problem) his beer and regularly smoked two packets of cigarettes a day (the famous Woodbine), he was a very serious professional, almost maniacal in his training and always looking for new plays to improve his game.

Famous was his debut with Newcastle.

Having arrived from Airdrie just a few days earlier, he was sent out on the pitch practically without ever training with his teammates.

Newcastle defender Charlie Spencer recounts that ‘when we saw him in the changing room just before we took the field against Everton we wondered if this little guy was really the one the club had just broken the piggy bank for. Then we stepped onto the pitch and after not even ten minutes I remember us looking at each other’s faces. Some were open-mouthed, some with a toothy grin and some with their thumbs raised in approval’.

Hughie Gallagher’s fiery and instinctive character put him more than once in conflict with opponents, teammates and football institutions.

Famous was his altercation with referee Fogg during a league game with Huddersfield. With Newcastle trailing by three goals to two (Gallagher’s double for Newcastle) in the final minutes of the game Gallagher was twice brought down in the box by opponents.

“Look at this referee! Don’t tell me you didn’t see that?” protested Gallagher.

“It’s not a penalty. Play Gallagher,” Mr. Fogg replied dryly.

“Everyone saw it but you!” an angry Gallagher echoes him.

“Fine. I’ll put that on the scoresheet” is the retort of the impassive black jacket.

At this point Gallagher completely loses his temper. At the final whistle he chased the referee into the locker room and shouted to him to the laughter of the crowd. “Fogg is your name and you were in the fog for the whole game!”

Apparently he even pushed the still-clothed referee into the changing room bath.

Two months disqualification, the inability to train with the team and no salary for the duration of the disqualification.

At this point Gallagher returned to Scotland, working for two months as a sports journalist for a Glasgow newspaper, ‘earning a lot more than I was getting as a player at Newcastle,’ Gallagher himself recounted.

With a player of that level, strong-arm tactics were often the only way to limit him. Several of his teammates recount that often at half-time Gallagher, while smoking his Woodbine, would have his socks and shoes soaked in blood from the beating he had received during the first half.

He would finish his cigarette, throw some cold water on his battered legs and return to the pitch, even more determined to score and win the match.

It is only a few years ago that the dramatic account of that terrible quarrel led Gallagher to suicide. It was his eldest son Hughie Junior who told the Chronicle everything a few years ago.

“I feel responsible for my father’s death. I made a mistake that night and I still carry the remorse inside me today. When I entered the house and saw Matt bleeding I was so angry that I could not reason. And when the neighbour asked me if he should call the police I said yes, without thinking for a second.

After all, it was just a nasty quarrel as happens in many families. My father was desperate and kept apologising, saying that he absolutely did not mean to hit Matt, that it was just an act of anger.

Matt could be stubborn and insolent when he chose to be but I have never seen my father lift a finger against him before.

When I told him to leave and that I didn’t want him to show his face in that house any more I know I gave him the cold shoulder. I regretted that sentence for years and will always regret it.

When our mother died in 1951 it was very hard for everyone but he took care of us by doing everything he could. He allowed us to study and follow our own paths. I did not see my father for several days after that night.

I was told that they had seen him around Gateshead, looking confused and bewildered.

But when the police warned me about what had happened I didn’t want to believe it.

I thought it would all settle down, that it was only a matter of time.

Instead, I will carry the weight of all those wrong decisions inside me forever.

Finally the memory of Alan Shearer, one who knows well the love of the Newcastle fans.

“One day my dad said to me: ‘Son, it doesn’t matter how many goals you score with Newcastle. You will never be as big as Hughie Gallagher’.