CARLOS JOSE’ CASTILHO: the tragic Fluminense legend

“Sweating the jersey, shedding tears and giving blood for Fluminense many did. Sacrificing a piece of his own body only one did: Castilho.”

This is what one reads upon entering the headquarters of ‘Flu’, one of the most popular and beloved teams in all of Brazil and Rio de Janeiro in particular.

But who is this Castilho and what has he done to deserve such a commendation?

It is 1957 and Fluminense is fighting for the title of the prestigious ‘Rio-Sao Paulo Tournament’, which since 1950 has pitted the best teams from the two main regional leagues, Rio de Janeiro’s ‘Carioca’ and the capital São Paulo’s ‘Paulista’.

For years, Castilho has been suffering from a problem in the little finger of his left hand, which has become difficult to manage in recent months.

After five fractures, the situation has become untenable.

A delicate surgical operation is required, which would probably put things right, but would also mean a long stop for rest and re-education.

Too much time for Castilho.

There is an important title at stake and Castilho certainly has no intention of ‘giving up’ at a time like this.

He asks the doctors if there is an alternative.

“Of course there is. Away with the finger, away with the pain, away with the problem!” the doctors tell him in an almost joking tone.

Castilho, however, has no intention of joking.

He inquires about the recovery times.

They are much faster than the recommended operation.

‘All he needs is for the wound to heal and he could eventually return to the field’.

That is exactly what Carlos José Castilho wants to hear.

Against the advice of everyone (Flu managers, team mates, friends and family) Castilho opts for this solution without any indecision.

Half of his left little finger will be amputated.

Two weeks later, he was on the pitch with his beloved ‘Tricolor’ … which won the ‘Copa Rio-Sao Paulo’ title for the first time in its history.

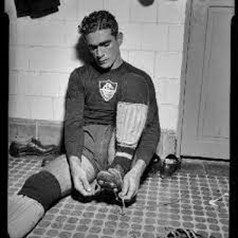

Carlos José Castilho was born in Rio de Janeiro in November 1927 and after starting out with the youth team of Olaria Atlético Clube in 1946, he was bought by Fluminense, where he soon made a name for himself as a goalkeeper with uncommon talents.

In addition to his remarkable physical prowess (he was 181 centimetres, an important size at the time), he was agile and extremely courageous.

To these qualities he added another one: an incredible ‘good fortune’ between the posts made of miraculous saves with all parts of the body, sensational and apparently impossible recoveries and posts and crossbars that regularly came to his aid even in the event of errors in position or intervention.

This ‘characteristic’ earned him two different nicknames: one for the ‘Flu’ fans, who renamed him Sâo Castilho (a kind of ‘saint’) for the opponents, on the other hand, is a more prosaic ‘leiteria’, which more or less sounds like ‘lucky’.

When the 1950 World Cup arrived, Castilho was included in the Brazilian national team’s squad called to finally win the highest trophy in football, and on friendly soil at that.

Castilho, at twenty-two years of age, is the youngest member of the team but does not hide his ambitions to play as a starter.

In front of him, however, is a goalkeeper of the value of Moacyr Barbosa to whom fortune will turn its back on in that World Cup, making him (unjustly) the scapegoat of Brazil’s failure.

Barbosa soon fell into oblivion and although he continued to play at excellent levels in his Vasco de Gama side in 1951, after their triumph in the Carioca Championship, it was Castilho who took his place on the national team.

With ‘Sâo Castilho’ between the posts, Brazil triumphed in 1952 in the Pan-American Championship played in Chile with Uruguay, Chile, Peru, Mexico and Panama in attendance.

It was the first important victory outside the national borders for Brazil, which with Castilho as an unquestionable starter went to Switzerland for the 1954 World Championship with renewed hopes of success.

Hopes that were dashed against the ‘Golden Team’, that is, the legendary Hungary of Puskas, Koscis and Hidegkuti, which the Brazilians ran into in the quarter-finals.

A potentially beautiful and spectacular match will instead turn into an unpleasant football spectacle, repeated fouls and seamless cautions and expulsions.

Hungary will prevail by four goals to two and for Brazil the World Cup triumph will be further postponed.

A triumph that would come four years later in Sweden, even though in the meantime the phenomenal Gylmar dos Santos Neves, known to the world as ‘Gilmar’ probably the best Brazilian goalkeeper in history, had arrived on the scene.

Castilho will be present in that World Cup as he will be in the following ones in 1962 but on both occasions without ever taking the field.

He would continue to play for Fluminense for many more seasons, winning the Carioca Championship with the ‘Tricolor’ in both 1959 and 1964.

He left the club the following year for a brief spell with Paysandu before hanging up his gloves at the age of 38.

He later embarked on a fairly successful coaching career, achieving flattering results with Esporte Club Vitòria and especially with São Paulo’s Santos, which he led to a triumph in the Paulista Championship in 1984.

Shortly after that triumph, however, a difficult period began in Castilho’s life.

The separation from his wife and the unexpected difficulty in finding a new team after the excellent results with Santos plunged him into a terrible state of depression.

Carlos Josè Castilho ended his life on 2 February 1987, at only fifty-nine years of age, by throwing himself from the flat in which his ex-wife lived.

Despite all the inferences, it is his brother Antonio himself who admits that no one in the family can really explain the reasons for that gesture.

At Fluminense, no one has ever forgotten him and for anyone who does not know his story, there is a bust of him at the entrance, with the words with which we started this article, which cannot fail to move anyone passing through those parts.

ANECDOTES AND CURIOSITIES

Having said his famous ‘luck’ between the posts, Castilho had another decidedly peculiar characteristic for a goalkeeper: he was glaringly colour-blind.

He considered this to be a great advantage with yellow balls, which he saw as ‘red’, saying that this favoured his ability to parry them, whereas he admitted to great difficulties in night matches with white balls.

One of his main characteristics was his great skill on penalty kicks. There were dozens that he managed to save during his career and in 1952 alone he managed to save six.

Castilho holds the record for the number of appearances with Fluminense, a team in which he played for eighteen seasons.

No less than 698 appearances in which he conceded 777 goals while keeping his goal unbroken for 255 games, which, considering the goalscoring averages of the period, is a truly excellent result.

At the end of his career, as mentioned, he played one season in Paysandu, enough to have him elected by the Belém fans as the best goalkeeper in the club’s history.

That season, in fact, Paysandu won the state championship, named ‘Paraense’, and Castilho was decisive with his performances.

One of the most important successes in the history of Fluminense and Castilho is that of the ‘Copa Rio’ in 1952.

This tournament, renamed then as the ‘World Club Championship’, which had been created the year before, involved eight teams from different countries, both South American and European.

In the first edition, Palmeiras triumphed, defeating Boniperti and Parola’s Juventus in the final.

In this second edition, which saw the participation of Sporting Lisbon, Peñarol, Grasshoppers, Austria Vienna, Corinthians, Libertad and Saarbrücken in addition to Fluminense, the final was played, in a return match, between the two Brazilian teams.

In fact, Fluminense had got the better of the formidable Peñarol of Schiaffino, Andrade and Ghiggia in their group, while for Corinthians, who had the very young Gilmar in goal, the most hostile opponent turned out to be Austria Vienna of the great Ernst Ocwirk.

It was their prowess in the two finals (a two-nil win for the ‘Flu’ in the first and a two-two draw in the second) that earned them the two nicknames that Castilho would carry with him for the rest of his career: Sâo Castilho for the Fluminense ‘torcida’ and ‘Leiteria’ for the opposition.